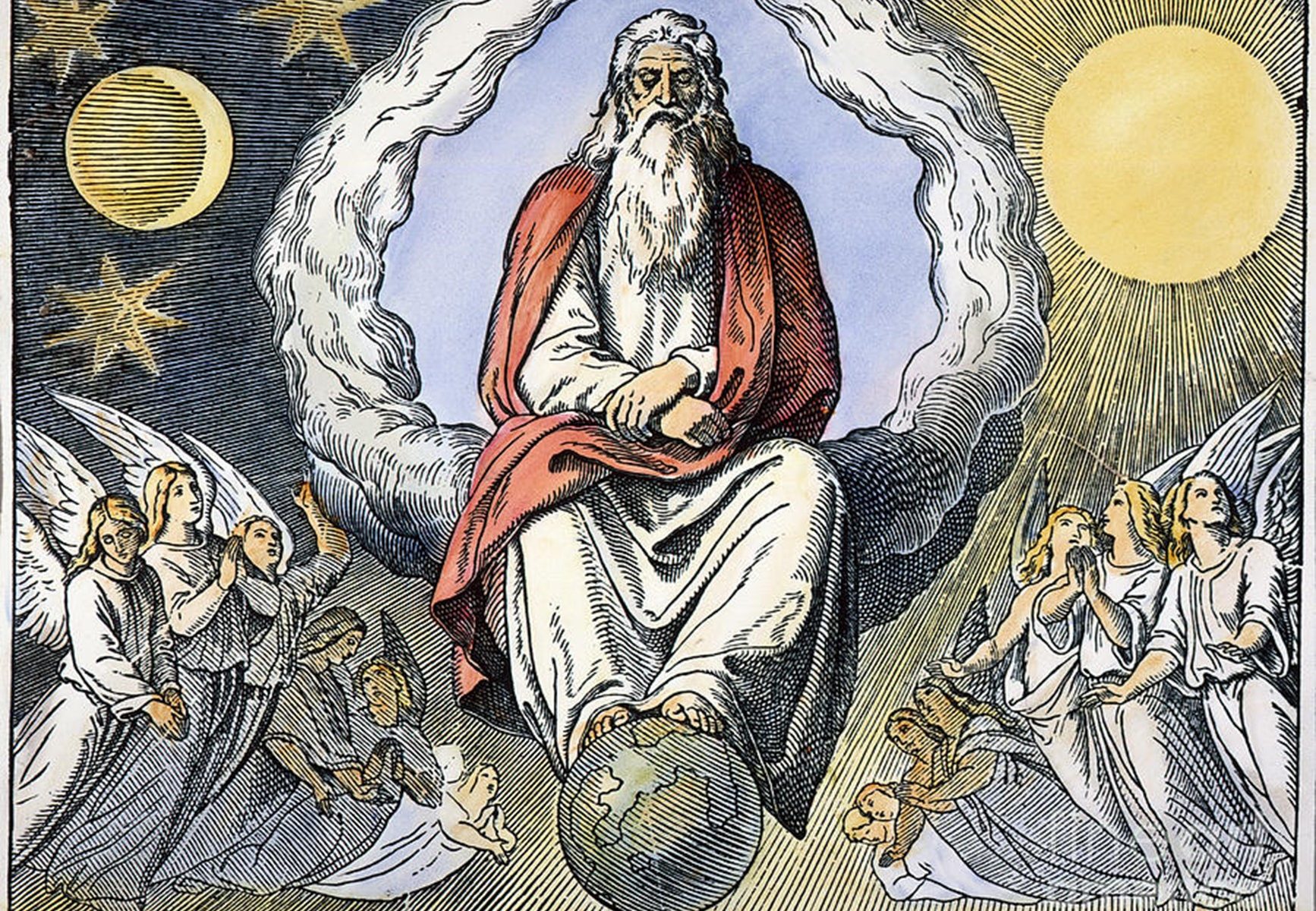

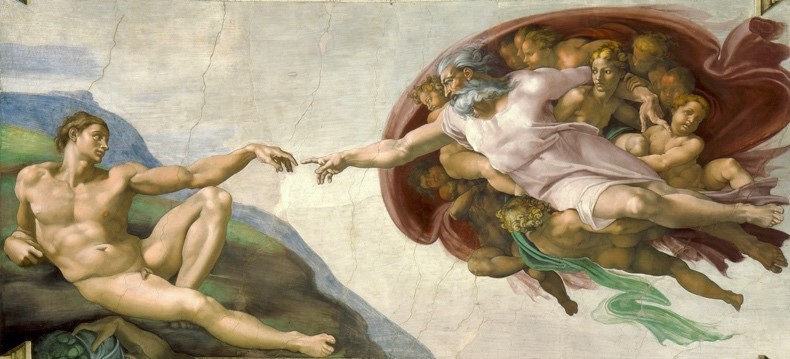

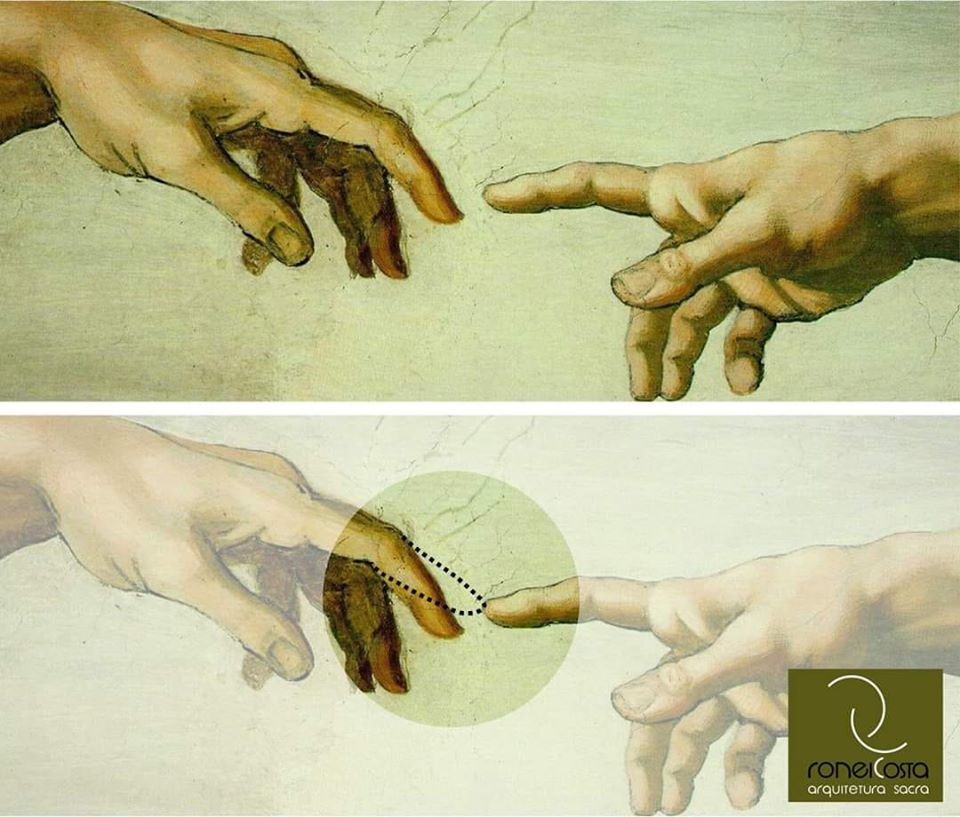

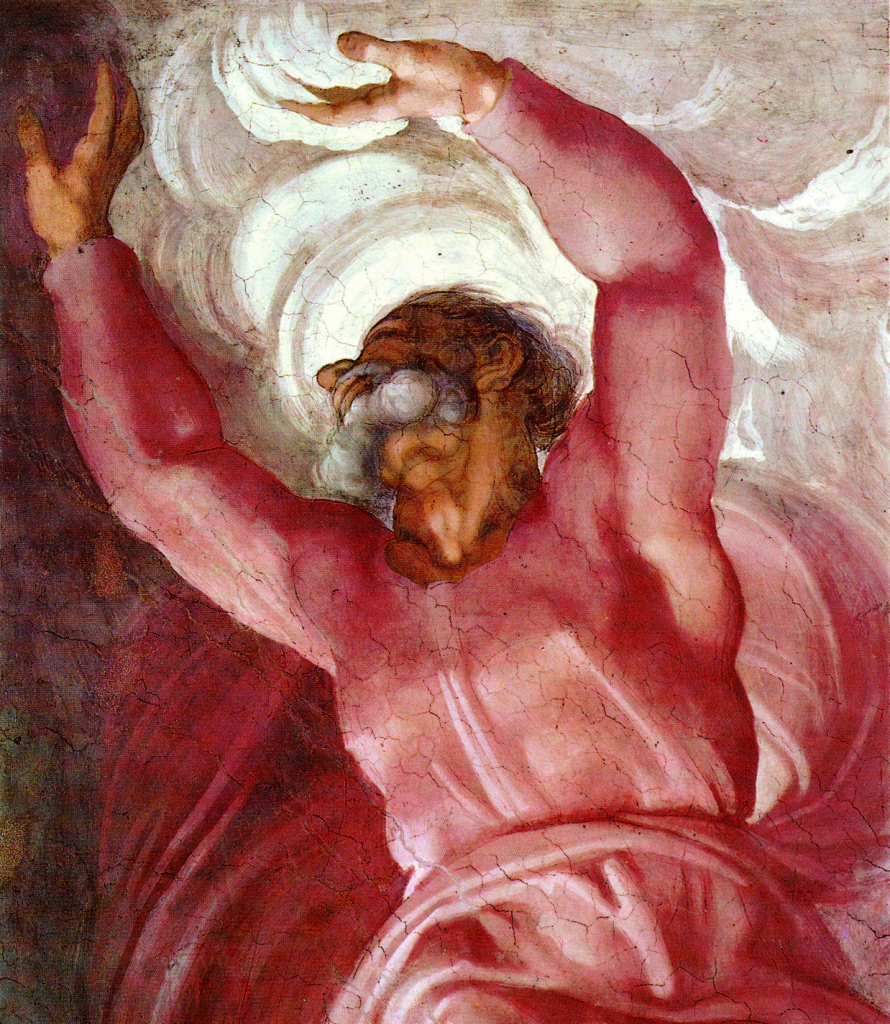

“And I, the Lord God, caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam. … And the rib which I, the Lord God, had taken from man, made I a woman.”1 Giorgio Vasari describes the scene above by contrasting the poses of Adam and Eve: “One [is] almost dead from being imprisoned by sleep, while the other comes alive completely reawakened by the benediction of God. The brush of this most ingenious artisan reveals the true difference between sleep and awakening, as well as how stable and firm His Divine Majesty may appear when speaking in human terms.”2

Upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that the symbolism of the painting extends beyond the Creation and looks forward to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and the birth of the Church that would carry out the divine commission to carry the Gospel to the world. In his analysis of the painting, Gary A. Anderson notes some details that are “highly unusual”:

Adam lies slumped around a dead tree, an odd sight for a luxuriant garden where death was, as of yet, unknown. The only way to understand this tired figure is to see him as a prefigurement of Christ, the “second Adam,” who was destined to hang on a barren piece of wood. “The sleep of [Adam],” the fourth-century theologian St. Augustine observed, “clearly stood for the death of Christ.”3 … If this is how we are to read this image of Adam, perhaps a similar interpretation holds for Eve.

To get our bearings on this we must bear in mind two facts. First, Mary as the “second Eve” is she who gives birth to Christ. Second, Mary as the “symbol of the church” is she who emerges from the rib of Christ on the Cross[, symbolized by the blood and water that issued from His side]. In this central panel of the Sistine ceiling, we see both the first and second Eve emerging from the ribs of Adam. …

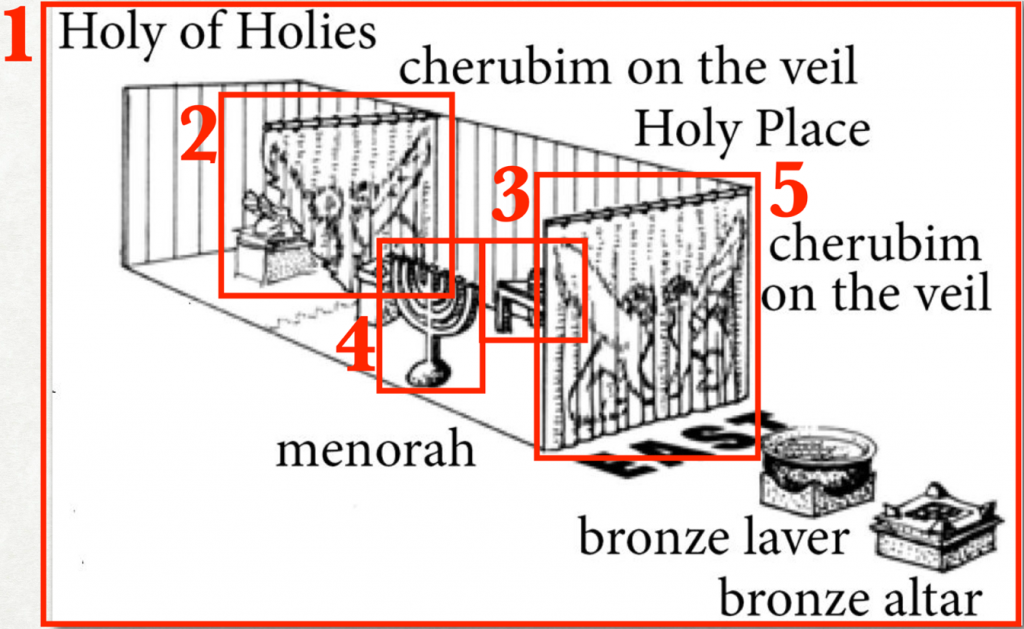

Further support for this comes from the history of the chapel itself. It was built on the model of Solomon’s Temple and was dedicated on August 15, 1483, the feast day of the Assumption and Coronation of the Virgin Mary in Heaven. A favored image of Mary in Christian devotional practice was Mary as the ark or tabernacle of God. Like the Ark of the Covenant in the Old Testament, the throne upon which God almighty took his seat, Mary was the seat in which God took human form. Like the Temple itself, she housed the verum corpus or the “true body” of God.”4 Significantly, this image is the center point of the entire chapel ceiling.

Having touched on the beautiful symbology that illustrates the central roles of Eve and Mary in the plan of salvation, this Essay will now explore the crucial interrelationships of men and women — and, in turn, their relationship to the rest of Creation— through the lens of the Restored Gospel.

The Intended “Oneness” of Man and Woman in Time and Eternity

Up to the point where Adam is formed, the order of Creation is decidedly hierarchic. However, the final creative act, where a rib is separated out from the man to make the woman,5 is portrayed in a fashion that demonstrates the relationship of Adam and Eve as “equal partners.”6 President Spencer W. Kimball taught that: “The story of the rib, of course, is figurative.”7 Nahum Sarna elaborates: “The mystery of the intimacy between husband and wife and the indispensable role that the woman ideally plays in the life of man are symbolically described in terms of her creation out of his body. The rib taken from man’s side thus connotes physical union and signifies that she is his companion and partner, ever at his side.”8

Other textual clues also set this creative act apart from all the rest. For one thing, we know that the man and the woman are created in the image of God—in other words, that they are both “after his kind.”9 And, just as important, we learn that since the man and the woman are not only of the same kind, but also bone of the same bone and flesh of the same flesh, they are not to separate from one other, but are to become “one” in a perfect unity that approaches identity.10 With the creation of Adam and Eve completed, God can declare His work as being not merely “good” (as He had done on previous days of Creation11 ), but rather as “very good.”12

In verse 27, we encounter two phrases that successively juxtapose the oneness and plurality of man and woman: “created I him” and “created I them.” In light of the interplay between “him” and “them” in this verse, one strand of rabbinic tradition proposes that “man was originally created male and female in one.” Thus, in the creation of woman, this tradition suggests that “God… separated the one (female) side,”13 a view that resembles Greek traditions that tell of originally androgynous humans who were split because of their rebellion, older Egyptian texts where the male earth god (Geb) and the female heaven (Nut) were separated in the beginning of Creation,14 and Zoroastrian texts that describe the couple as having been at first “connected together and both alike.”15 However, we think it more straightforward to conclude that the three lines of this stately poetic diction in the Book of Moses are structured as they are in order to successively draw our attention to three things:

1. to the creation of man in the Divine (“in our image, after our likeness”);

2. to the fact that this resemblance exactly parallels the one that exists between the Father and the Son (“in mine own image,” “in the image of mine Only Begotten”); and

3. to the essential distinction of gender (“male and female”).16

With specific respect to the oneness of man and woman in Latter-day Saint teachings, Elder Erastus Snow expressed that “there can be no God except he is composed of the man and woman united, and there is not in all the eternities that exist, nor ever will be, a God in any other way. There never was a God, and there never will be in all eternities, except they are made of these two component parts: a man and a woman, the male and the female.”17 This statement parallels a statement in the Jewish Talmud commenting that “a man without a wife is not a man, for it is said, ‘male and female He created them … and called their name Man’18 [i.e., only together, as man and wife, is he called ‘Man’].”19

“Male and Female”: The Eternal Nature of Gender

Both men and women are created in the divine image and likeness, which for even some non-Latter-day Saint scholars has implications not only for human nature but also for the character of God.20 The 1909 and 1925 First Presidency statements commenting on the origin of man both include the assertion that: “All men and women are in the similitude of the universal Father and Mother, and are literally the sons and daughters of Deity.”21

Though masculine verbs and adjectives are used with God’s name (also masculine), evidence exists that the Ugaritic goddess Asherah was sometimes worshipped as a female consort to Jehovah in preexilic times.22 Allusions to a female deity are also seen by some in biblical references to Wisdom23 and in the texts of mystic Judaism referring to the Shekhinah.24 Although Jeremiah spoke out against the worship of the “queen of heaven,”25 Daniel Peterson points out that prophetic opposition to the idea does not seem to appear before the eighth century BCE.26 From his study of this verse, the eminent biblical scholar David Noel Freedman concludes: “Just as the male God is the model and image for the first man, so some divine or heavenly female figure serves as the model and likeness for the human female, the first woman.”27

Is gender an essential, primordial attribute of every human being? The First Presidency’s proclamation on the family clearly affirms that gender is an eternal aspect of the spiritual identity of each individual.28 This is consistent with Elder James E. Talmage’s 1914 statement: “Children of God have comprised male and female from the beginning. Man is man and woman is woman, fundamentally, unchangeably, eternally.”29

Bill T. Arnold further observes that the terms “male and female” used for Adam and Eve “emphasize their sexuality in a way ‘man and woman’ would not.”30 Sarna further notes:31

No … sexual differentiation is noted in regard to animals. … The next verse shows [human sexuality] to be a blessed gift of God woven into the fabric of life. As such, it cannot of itself be other than wholesome. By the same token, its abuse is treated in the Bible with particular severity. Its proper regulation is subsumed under the category of the holy, whereas sexual perversion is viewed with abhorrence as an affront to human dignity and as a desecration of the divine image of man.

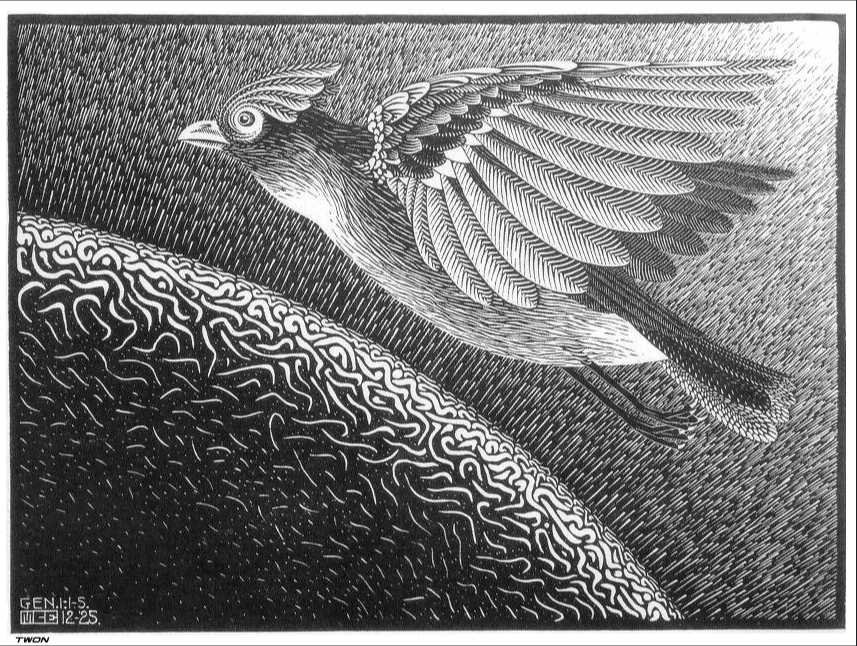

“Be Fruitful, and Multiply, and Replenish the Earth”

The Hebrew phrase for “be fruitful and multiply” (peru urebu) may be a deliberate play on the “without form and void” (tohu vabohu) of v. 2: “In this case, the living creatures of God’s Creation are hereby empowered to perpetuate God’s life-giving creativity by bringing still more life into the world, by filling up and inhabiting that which was previously empty and uninhabitable.”32 “The difference between the formulation here and God’s blessing to the fish and fowl in verse 22 is subtle and meaningful. Here God directly addresses man and woman.”33

The word “replenish” can be misleading to modern English speakers. While it is often used today to mean “refill,” the Hebrew term male means simply to “fill” or “make full.” Thus, Sarna renders the command in this verse as “Be fertile and increase, fill the earth.”34 Laurence Turner observes that although keeping this commandment will not be easy in light of the pain of childbirth,35 the murderous dispositions of some men,36 the threat of famine and floods,37 and the failure of mankind to disperse and “fill the earth” as they were commanded to do,38 the book of Genesis demonstrates that “God intervenes to make sure it is obeyed, willingly or not.”39

Importantly, Roger R. Keller notes that the commandment anticipates the departure of Adam and Eve from Eden, since they “were commanded to multiply and replenish the earth, not the Garden.”40

“Subdue [the Earth], and Have Dominion … Over Every Living Thing”

The commandment to “subdue” the earth conveys the idea of settlement and agriculture, as described in Moses 3:5, 15.41 In light of subsequent events in Genesis, Turner concludes:42

Although humans increasingly dominate the animal creation and eventually rule despotically (an intensification of the original command), there is an ironic sense in which animals, through the serpent, exercise an ongoing dominion over the humans (a reversal of the original command). … Also, the earth becomes increasingly difficult to dominate. It overwhelms most of humanity in the Flood, and all of humanity in death.

Elaborating on the traditional description of humankind’s “dominion,” the pseudepigraphal Cave of Treasures has God speaking the following words to Adam: “Adam, behold; I have made thee king, and priest, and prophet, and lord, and head, and governor of everything which hath been made and created; and they shall be in subjection unto thee, and they shall be thine, and I have given unto thee power over everything which I have created.”43

However, challenging common misunderstandings of what this concept means in practice, Hugh W. Nibley comments: “A favorite theme of Brigham Young was that the dominion God gives man is designed to test him, to enable him to show to himself, his fellows, and all the heavens just how he would act if entrusted with God’s own power; if he does not act in a godlike manner, he will never be entrusted with a Creation of his own, worlds without end.”44 Similarly, James E. Faulconer observes that “in ruling over the world, humans are its gods, those through whom Creation is either condemned or destroyed. In this, humans are like God: we and the world are judged through our dominion; God and the world are justified by His.”45

Nibley further observes that the word “dominion” comes from the Latin dominus (“lord”), “specifically ‘the lord of the household,’ in his capacity of generous host … [responsible as] master for the comfort and well-being of his dependents and guests.”46 According to Sarna, the word expresses:

the coercive power of the monarch, consonant with the explanation just given for “the image of God.” This power, however, cannot include the license to exploit nature banefully, for the following reasons: the human race is not inherently sovereign, but enjoys its dominion solely by the grace of God. Furthermore, the model of kingship here presupposed is Israelite, according to which … the limits of [the rule of the monarch] are carefully defined and circumscribed by divine law, so that kingship is to be exercised with responsibility and is subject to accountability. Moreover, man, the sovereign of nature, is conceived at this stage to be functioning within the context of a “very good” world in which the interrelationships of organisms with their environment and with each other are entirely harmonious and mutually beneficial, an idyllic situation that is clearly illustrated in Isaiah’s vision of the ideal future king.47 Thus, despite the power given him, man still requires special divine sanction to partake of the earth’s vegetation, and although he “rules” the animal world, he is not here permitted to eat flesh.48

To have “dominion” in the priesthood sense means to have responsibility,49 specifically as God’s representative on earth.50 As Nibley succinctly puts it: “Man’s dominion is a call to service, not a license to exterminate.”51

Conclusion

The effects of the inception of light and its division from darkness “in the beginning” cascade through the remaining days of Creation as each episode recounts the successive generation of new and finer-grained distinctions that define created elements through the principle of separation.52 Indeed, the process of division and separation began even before the Creation, when those who kept their first estate were separated from those who did not.53 Moreover, the theme continues after the ending of the Creation account, as the focus of the narrative moves from the actions of God to those of Adam and Eve. Exercising the agency that has been granted them, they partake of the forbidden fruit, and are cast out of the Garden, experiencing an immediate separation from the presence of God and, eventually, a separation of body and spirit at death.

Explaining that the principles of division and separation that drive the dynamics of Creation are not meant to govern the relationship of husband and wife, God declared “that it was not good that man should be alone.”54 Indeed, as Catherine Thomas observes, a primary objective of mortality seems to have been precisely “to foster the conditions in which the man and the woman may achieve interdependence,” thus affording each individual an opportunity to rise to “the challenge of not only perfecting ourselves individually but also perfecting ourselves in relationships. .… Relationships were given to us to develop us in love.”55

That the opportunity to perfect ourselves in relationships necessarily extends beyond our family circle is witnessed by this statement from the Prophet Joseph Smith:56

Love is one of the chief characteristics of Deity, and ought to be manifested by those who aspire to be the sons of God. A man filled with the love of God, is not content with blessing of his family alone, but ranges through the whole world, anxious to bless the whole human race.

And, going further, should not our love of all God’s children be further enlarged to encompass “all creatures of our God and King.”?57

This article is adapted and updated from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. www.templethemes.net, pp. 87, 89, 114–117, 127, 180–182.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 87, 89, 114–117, 127, 180–182.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 211–217.

Hafen, Bruce C., and Marie K. Hafen. “Crossing thresholds and becoming equal partners.” Ensign 37, August 2007, 24-29.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1972. “Man’s dominion or subduing the earth.” In Brother Brigham Challenges the Saints, edited by Don E. Norton and Shirley S. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 13, 3-22. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1980. “Patriarchy and matriarchy.” In Old Testament and Related Studies, edited by John W. Welch, Gary P. Gillum and Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 1, 87-113. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, pp. 224–230.

References

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Arnold, Bill T. Encountering the Book of Genesis. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998.

———. Genesis. New Cambridge Bible Commentary, ed. Ben Witherington, III. New York City, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Augustine. ca. 410. “The City of God.” In Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, edited by Philip Schaff. 14 vols. Vol. 2, 1-511. New York City, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1887. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994.

Barker, Margaret. Where shall wisdom be found? In Russian Orthodox Church: Representation to the European Institutions. http://orthodoxeurope.org/page/11/1/7.aspx. (accessed December 24, 2007).

———. The Revelation of Jesus Christ: Which God Gave to Him to Show to His Servants What Must Soon Take Place (Revelation 1.1). Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 2000.

———. “Wisdom, the Queen of Heaven.” In The Great High Priest: The Temple Roots of Christian Liturgy, edited by Margaret Barker, 229-61. London, England: T & T Clark, 2003.

———. Temple Theology. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2004.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

Barney, Kevin L. Do we have a Mother in Heaven? In Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research (FAIR). http://www.fairlds.org/pubs/MotherInHeaven.pdf. (accessed December 24, 2007).

Blech, Benjamin, and Roy Doliner. The Sistine Secrets: Michelangelo’s Forbidden Messages in the Heart of the Vatican. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2008.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. www.templethemes.net.

Budge, E. A. Wallis, ed. The Book of the Cave of Treasures. London, England: The Religious Tract Society, 1927. Reprint, New York City, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Cannon, Elaine Anderson. “Mother in Heaven.” In Encyclopedia of Mormonism, edited by Daniel H. Ludlow. 4 vols. Vol. 2, 961. New York City, NY: Macmillan, 1992.

Cassuto, Umberto. 1944. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 1: From Adam to Noah. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1998.

Christensen, Kevin, and Shauna Christensen. “Nephite Feminism Revisited: Thoughts on Carol Lynn Pearson’s View of Women in the Book of Mormon.” FARMS Review of Books 10, no. 1 (1998): 9-61. http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/pdf.php?filename=MjQ3Njk2NDg3LTEwLTIucGRm&type=cmV2aWV3. (accessed December 24).

Cohen, Abraham, ed. The Soncino Chumash: The Five Books of Moses with Haphtaroth. London: The Soncino Press, 1983.

De Vecchi, Pierluigi, and Gianluigi Colalucci. Michelangelo: The Vatican Frescoes. Translated by David Stanton and Andrew Ellis. New York City, NY: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1996.

Derr, Jill Mulvay, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher. Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992.

Faulconer, James E. “Adam and Eve—Community: Reading Genesis 2-3.” Journal of Philosophy and Scripture 1, no. 1 (Fall 2003). http://www.philosophyandscripture.org/Issue1-1/James_Faulconer/james_faulconer.html. (accessed August 10).

Freedman, David Noel. “The status and role of humanity in the cosmos according to the Hebrew Bible.” In On Human Nature: The Jerusalem Center Symposium, edited by Truman G. Madsen, David Noel Freedman and Pam Fox Kuhlken, 9-25. Ann Arbor, MI: Pryor Pettengill Publishers, 2004.

Friedman, Richard Elliott, ed. Commentary on the Torah. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2001.

Grant, Heber J., Anthony W. Ivins, and Charles W. Nibley. 1925. “”Mormon” view of evolution.” In Messages of the First Presidency, edited by James R. Clark. 6 vols. Vol. 5, 243-44. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1971.

Hafen, Bruce C. Covenant Hearts: Marriage and the Joy of Human Love. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Hafen, Bruce C., and Marie K. Hafen. “Crossing thresholds and becoming equal partners.” Ensign 37, August 2007, 24-29.

Hamblin, William J., and David Rolph Seely. Solomon’s Temple: Myth and History. London, England: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Hinckley, Gordon B. “Daughters of God.” Ensign 21, November 1991, 97-100.

Hinckley, Gordon B., Thomas S. Monson, and James E. Faust. “The family: A proclamation to the world. Proclamation of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve presented at the General Relief Society Meeting, September 23, 1995.” Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1995. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/the-family-a-proclamation-to-the-world/the-family-a-proclamation-to-the-world?lang=eng. (accessed August 16, 2020).

Holland, Jeffrey R. 1988. Of Souls, Symbols, and Sacraments. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2001.

Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985.

Jones, Gerald E. Animals and the Church. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2003.

Keller, Roger R. “Teaching the Fall and the Atonement: A comparative method.” The Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 5, no. 2 (2004): 101-18. http://rsc.byu.edu/TRE/TRE5_2.pdf. (accessed September 1).

Kimball, Spencer W. “The blessings and responsibilities of womanhood.” Ensign 6, March 1976, 70-73. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/1976/03/the-blessings-and-responsibilities-of-womanhood?lang=eng. (accessed September 7, 2020).

———. The Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1982.

Kugel, James L. “Some instances of biblical interpretation in the hymns and wisdom writings of Qumran.” In Studies in Ancient Midrash, edited by James L. Kugel, 155-69. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Meeks, Wayne A. “The image of the androgyne: Some uses of a symbol in earliest Christianity.” History of Religions 13, no. 3 (February 1974): 165-208.

Müller, F. Max. “Bundahis.” In Pahlavi Texts: The Bundahis, Bahman Yast, and Shayast La-Shayast (including Selections of Zad-sparam), edited by F. Max Müller. 5 vols. Vol. 1. Translated by E. W. West. The Sacred Books of the East 5, ed. F. Max Müller, 1-151. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1880. Reprint, Kila, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2004.

Neusner, Jacob, ed. Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation. 3 vols. Vol. 1: Parashiyyot One through Thirty-Three on Genesis 1:1 to 8:14. Brown Judaic Studies 104, ed. Jacob Neusner. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1972. “Man’s dominion or subduing the earth.” In Brother Brigham Challenges the Saints, edited by Don E. Norton and Shirley S. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 13, 3-22. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

———. 1988. “The meaning of the atonement.” In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 554-614. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Oaks, Dallin H. “The great plan of happiness.” Ensign 23, November 1993, 72-75.

Paulsen, David L. “Are Christians Mormon? Reassessing Joseph Smith’s theology in his bicentennial.” BYU Studies 45, no. 1 (2006): 35-128.

Peterson, Daniel C. “Nephi and his Asherah: A note on 1 Nephi 11:8-23.” In Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, edited by Davis Bitton, 191-243. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1998.

Plato. after 385 BCE. “Symposium (The Banquet).” In Great Dialogues of Plato, edited by Eric H. Warmington and Philip G. Rouse. Translated by W. H. D. Rouse, 69-117. New York City, NY: New American Library, 1956.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Seaich, John Eugene. Ancient Texts and Mormonism: Discovering the Roots of the Eternal Gospel in Ancient Israel and the Primitive Church. 2nd Revised and Enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: n. p., 1995.

Smith, Joseph F., J. R. Winder, and A. H. Lund. 1909. “The origin of man.” In Messages of the First Presidency, edited by James R. Clark. 6 vols. Vol. 4, 199-206. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1970.

Smith, Joseph Fielding, Jr. 1931. The Way to Perfection: Short Discourses on Gospel Themes Dedicated to All Who Are Interested in the Redemption of the Living and the Dead. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Genealogical Society of Utah, 1935.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1840. Letter, Hancock County, Illinois, to the Quorum of the Twelve, England, 15 December 1840. In The Joseph Smith Papers. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-quorum-of-the-twelve-15-december-1840/. (accessed September 28, 2020).

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Snow, Erastus. 1878. “There is a God; communion with Him an inherent craving of the human heart; man in his image; male and female created he them; spirit and flesh; mortal and immortal (Discourse delivered in the meetinghouse, Beaver City, Beaver county, Utah, on Sunday Morning, 3 March 1878).” In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 19, 266-79. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Stratton, Richard D., ed. Kindness to Animals and Caring for the Earth. Portland, OR: Inkwater Press, 2004.

Talmage, James E. “The eternity of sex.” Young Woman’s Journal 25, October 1914, 600-04. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/YWJ/id/17248/rec/25. (accessed 27 September 2020).

Thomas, M. Catherine. “Women, priesthood, and the at-one-ment.” In Spiritual Lightening: How the Power of the Gospel Can Enlighten Minds and Lighten Burdens, edited by M. Catherine Thomas, 47-58. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1996.

Turner, Laurence. Announcements of Plot in Genesis. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 96, ed. David J. A. Clines and Philip R. Davies. Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1990. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/14343346.pdf. (accessed July 28, 2017).

Wenham, Gordon J., ed. Genesis 1-15. Word Biblical Commentary 1: Nelson Reference and Electronic, 1987.

Zlotowitz, Meir, and Nosson Scherman, eds. 1977. Bereishis/Genesis: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources 2nd ed. Two vols. ArtScroll Tanach Series, ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1986.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. Public domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo,_Creation_of_Eve_00.jpg (accessed September 7, 2020).

1 Moses 3:21-22.

2 P. De Vecchi et al., Michelangelo, p. 151.

3 See Augustine, City, 22:17, p. 496.

4 G. A. Anderson, Perfection, pp. 5–8.

5 Moses 3:21-22.

6 G. B. Hinckley et al., The family: A proclamation to the world. Proclamation of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve presented at the General Relief Society Meeting, September 23, 1995. Cf. S. W. Kimball, Teachings (1982), 26 February 1977, p. 315. Compare B. Blech et al., Secrets, p. 202.

7 S. W. Kimball, Blessings, p. 71.

8 N. M. Sarna, Genesis, p. 22.

9 Moses 2:26-27.

10 Moses 3:23-24. See also J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Commentary 2:27-a, p. 115; J. R. Holland, Souls, pp. 17-18. Compare H. W. Nibley, Atonement, p. 568; M. Zlotowitz et al., Bereishis, p. 111.

11 Moses 2:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25.

12 Moses 2:31.

13 A. Cohen, Chumash, Genesis 2:21, p. 11. See J. Neusner, Genesis Rabbah 1, 8:1, p. 73. See W. A. Meeks, Androgyne, p. 185 for relevant discussion, including evidence that rabbis had access to a version of the Septuagint with the reading: “male and female created I him.”

14 Plato, Symposium, 189d-190a, pp. 85-87; H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, 7, pp. 88-89.

15 F. M. Müller, Bundahis, 15:2, p. 53. See references to related concepts in additional cultures in J. E. Seaich, Ancient Texts 1995, pp. 916-918.

16 Cf. U. Cassuto, Adam to Noah, pp. 57-58. See D. N. Freedman, Humanity, p. 23; J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Commentary 2:27-b, p. 115.

17 E. Snow, ES 3 March 1878, p. 270.

18 See Moses 6:10.

19 Yevamos 63a, cited in M. Zlotowitz et al., Bereishis, p. 167; cf. 1 Corinthians 11:11. See J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Endnote 2-19, p. 128.

20 See, e.g., R. E. Friedman, Commentary, pp. 16-17.

21 H. J. Grant et al., Evolution, p. 244; J. F. Smith et al., Origin, p. 203. Additional information relating to the Latter-day Saint concept of a “Mother in Heaven” can be found in K. L. Barney, Mother in Heaven; E. A. Cannon, Mother in Heaven; J. M. Derr et al., Relief Society, pp. 57-58, 449 nn. 129, 131; G. B. Hinckley, Daughters; D. L. Paulsen, Are Christians Mormon, pp. 96-107. Compare M. Barker, Christmas, pp. 39-44.

22 D. C. Peterson, Asherah 1998, pp. 202-209. See also e.g., Deuteronomy 16:21; 1 Kings 14:15, 23; 2 Kings 17:15-16.

23 Ḥokhmah in Hebrew, Sophia in Greek—see, e.g., Proverbs 8:1-31.

24 See, e.g., H. Schwartz, Tree, pp. 45-59.

25 Jeremiah 44:17ff.

26 D. C. Peterson, Asherah 1998, p. 201. See also M. Barker, Wisdom; M. Barker, Revelation, pp. 204-206; M. Barker, Queen; M. Barker, Temple Theology, pp. 75-93; D. N. Freedman, Humanity, pp. 22-25 (cited in J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Moses 2 Gleanings, pp. 122-123). For a discussion of related themes in the Book of Mormon, see K. Christensen et al., Nephite Feminism. For a brief summary of the role of female deities in Israelite worship, see, e.g., W. J. Hamblin et al., Solomon’s Temple, pp. 60-63.

27 D. N. Freedman, Humanity, p. 24. Some rabbinical sources see the female figure of Wisdom as assisting God in Creation, while others argue vehemently that God had no help of any kind (J. L. Kugel, Instances, pp. 160-162).

28 G. B. Hinckley et al., The family: A proclamation to the world. Proclamation of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve presented at the General Relief Society Meeting, September 23, 1995.

29 J. E. Talmage, Eternity of Sex, p. 602.

30 B. T. Arnold, Genesis, p. 35.

31 N. M. Sarna, Genesis, p. 13. See also J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Commentary 2:26-b, p. 112, 3:23-c, p. 183.

32 B. T. Arnold, Genesis 2009, p. 42.

33 N. M. Sarna, Genesis, p. 13.

34 Ibid., p. 13.

35 See Moses 4:22.

36 See Moses 5:31-32, 47; 6:15; 8:18.

37 See Moses 8:4, 30.

38 See Genesis 11:1-9.

39 L. Turner, Announcements, p. 49.

40 R. R. Keller, Teaching, p. 103. Cf. D. H. Oaks, Plan, p. 73; 2 Nephi 2:23.

41 V. P. Hamilton, Genesis 1-17, p. 140. Cf. Doctrine and Covenants 26:1. On dominion, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Commentary 2:26-d, p. 114.

42 L. Turner, Announcements, pp. 48-49.

43 E. A. W. Budge, Cave, p. 53.

44 H. W. Nibley, Dominion, p. 10.

45 J. E. Faulconer, Adam and Eve, 7. For collections of statements from secular and religious sources on man’s stewardship for animals and for the earth, see G. E. Jones, Animals; R. D. Stratton, Kindness.

46 H. W. Nibley, Dominion, p. 7.

47 Isaiah 11:1-9.

48 N. M. Sarna, Genesis, pp. 12-13. See Moses 2:29-30; cf. Genesis 9:3-4.

49 J. F. Smith, Jr., Way 1935, p. 221.

50 G. J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, pp. 30-31; Hirsch, cited in M. Zlotowitz et al., Bereishis, p. 70.

51 H. W. Nibley, Dominion, p. 18; cf. T. L. Brodie, Dialogue, p. 136.

52 See J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 85-87, 127 n. 2-15.

53 Abraham 3:26-28.

54 Moses 3:18.

55 M. C. Thomas, Women, pp. 54, 55, 56. Elder Bruce C. Hafen also discusses the importance of husbands and wives becoming interdependent, equal partners in marriage, as contrasted with the ideas of independence or dependence. See B. C. Hafen, Covenant, p. 174; B. C. Hafen et al., Crossing, p. 26.

56 J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 15 December 1840, p. 174. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Letter to the Twelve, 15 December 1840, p. [2].

57 Hymns (1985), Hymns (1985), #62.