Book of Abraham Insight #38

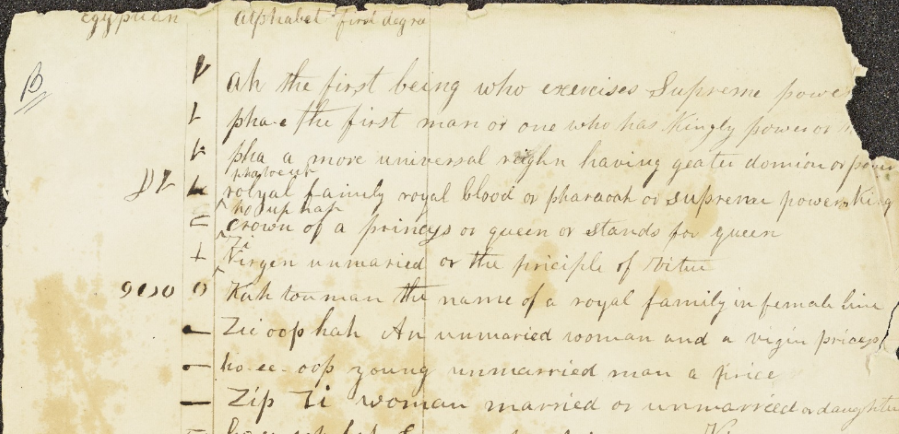

Associated with the translation of the Book of Abraham is a collection of documents known today as the Kirtland Egyptian Papers.1 This name was coined by Hugh Nibley in the early 1970s to describe a corpus of manuscripts that can be classified into, broadly, two categories: Book of Abraham manuscripts and Egyptian-language manuscripts.2 Although still commonly used, because some of these documents post-date the Kirtland period of Latter-day Saint history, and because it is somewhat vague, the name coined by Nibley to describe this corpus has fallen out of use among scholars who prefer more precise classifications. What’s more, “The[se] name designations are modern ones and typically reflect assumptions of the individuals using the particular designations. No [single] designation [to describe these texts] has gained wide acceptance.”3

Notwithstanding, as mentioned above, this corpus “can be divided into two fairly distinct parts: “(1) those papers that center primarily on the text of the Book of Abraham and (2) those that focus on alphabet and grammar material that the authors connected to the ancient Egyptian language.”4 The Abraham manuscripts (1) are what contain the extant English text of the Book of Abraham. These manuscripts date from between mid-1835 to early-1842 and are in the handwriting of W. W. Phelps, Warren Parrish, Frederick G. Williams, and Willard Richards.5 The Egyptian-language manuscripts (2) are comprised of a hodgepodge of documents that transcribe portions of the characters from the Egyptian papyri and appear to attempt to systematize an understanding of the Egyptian language in the handwriting of W. W. Phelps, Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and Warren Parrish.6 While these two groups can be broadly distinguished, “it should also be understood that the Abraham documents contain a certain amount of Egyptian material and the Egyptian papers include a certain amount of Abraham material.”7 Because of this, it is clear that there is some kind of relationship between these two groups.

Although there is an apparent relationship between these two groups of documents, because of conflicting interpretations of the historical data among scholars “almost every aspect of these documents is disputed: their authorship, their date, their purpose, their relationship with the Book of Abraham, their relationship with the Joseph Smith Papyri, their relationship with each other, what the documents are or were intended to be, and even whether the documents form a discrete or coherent group.”8 This uncertainty has unfortunately resulted in a lack of consensus on how to understand this collection.

Although it is clear that the Egyptian-language documents in the Kirtland Egyptian Papers reflect a sincere attempt by those involved to somehow understand the Egyptian language (there is no evidence for conscious fraud or deceit on the part of those involved), “like many similar efforts of the time to unravel the mysteries of the Egyptian language, these attempts are considered by modern Egyptologists—both Latter-day Saints and others—to be of no actual value in understanding [the] Egyptian” language.9 Because of this, some have attempted to use the Egyptian-language documents to cast doubt on Joseph Smith’s prophetic inspiration or the authenticity of the Book of Abraham. This effort, however, is highly questionable for many reasons.

First, “The extent of Joseph Smith’s involvement in the creation of these manuscripts is unknown.”10 While it is true that he had some involvement in the project since his handwriting appears in one manuscript and his signature on another,11 there is not enough evidence to conclusively demonstrate that Joseph Smith was the driving instigator behind the effort to create a systematized grammar of the Egyptian language.

Second, “It is unclear when in 1835 Joseph Smith began creating the existing Book of Abraham manuscripts or what relationship the Book of Abraham manuscripts have to the Egyptian-language documents.”12

Third, while “considerable overlap of themes exists between the Book of Abraham and the Egyptian-language documents . . . most of the Book of Abraham is not textually dependent on any of the extant Egyptian-language documents. The inverse is also true: most of the content in the Egyptian-language documents is independent of the Book of Abraham.”13

Fourth, and finally, the Egyptian-language documents were never presented as authoritative revelation similar to Joseph Smith’s other canonized books of scripture. “What emerges most clearly from a closer look at the Kirtland Egyptian Papers is the fact that there is nothing official or final about them—they are fluid, exploratory, confidential, and hence free of any possibility or intention of fraud or deception.”14

Rather than viewing the Egyptian-language documents as Joseph Smith’s botched revelation, they might instead more plausibly be seen as part of “an interest in ancient languages within the early church and an anticipation that additional ancient texts would be revealed.”15 This interest prompted Joseph Smith and those close to him to attempt a secular study of other ancient languages such as Hebrew and Greek.16 The Egyptian-language project undertaken by some early Latter-day Saints and associated with the coming forth of the Book of Abraham may very well be situated in that same context.

There is still much that we do not know about the so-called Kirtland Egyptian Papers, including the precise circumstances surrounding their creation and purpose. While their ultimate nature remains debated, the work of scholars in recent years has called into question older assumptions and arguments about the extent of Joseph Smith’s participation in the Egyptian-language project and the Book of Abraham’s dependency on these manuscripts. In the mean time, what can be safely concluded is that “although we have incomplete information on exactly how the Book of Abraham was translated, the resulting contents of that translation are more important than the process itself.”17

Further Reading

John Gee, “Joseph Smith and the Papyri,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 13–42.

Brian M. Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project: ‘A Knowledge of Hidden Languages’,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 474–511.

Hugh Nibley, “The Meaning of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers,” BYU Studies 11, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 350–399; reprinted in An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2009), 502–568.

Footnotes

1 Hugh Nibley, “The Meaning of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers,” BYU Studies 11, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 350–399; reprinted in An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2009), 502–568.

2 Brian M. Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project: ‘A Knowledge of Hidden Languages’,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 447–449.

3 John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 32–33.

4 Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project,” 477.

5 Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project,” 477–478; Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 34–35.

6 Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project,” 478; Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 34–35. The Book of Abraham manuscripts and related Egyptian-language documents can be viewed online at the Joseph Smith Papers website.

7 Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project,” 477.

8 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 33.

9 Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2018), xxv.

10 Jensen and Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, xv.

11 Jensen and Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, xv; Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 34.

12 Jensen and Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, xxv. For different arguments on the direction of the dependency between the Book of Abraham and the Egyptian-language documents, see Hauglid, “The Book of Abraham and the Egyptian Project,” 474–511; Kerry Muhlestein, “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 33–37.

13 Jensen and Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, xxv.

14 Nibley, “The Meaning of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers,” 399.

15 Jensen and Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, xxi.

16 See Matthew J. Grey, “‘The Word of the Lord in the Original’: Joseph Smith’s Study of Hebrew in Kirtland,” in Approaching Antiquity, 249–302; John W. Welch, “Joseph Smith’s Awareness of Greek and Latin,” in Approaching Antiquity, 303–328.

17 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 39.