Cuando Hugh Nibley estaba terminando el artículo final de agosto de 1977 perteneciente a su larga serie sobre los manuscritos antiguos de Enoc y Moisés 6–7 para la revista Ensign, recibió, “justo a tiempo”1, la tan esperada traducción al inglés de los fragmentos de los libros arameos de Enoc de la cueva 4 en Qumrán2. En su artículo, Nibley fue el primero en sugerir una correspondencia notable entre un personaje del Libro de los Gigantes llamado Mahaway3 (MHWY en arameo) y los nombres “Mahújah” (probablemente equivalente al hebreo MHWY o MḤWY) y “Mahíjah” (posible analogía de MHYY o MḤYY) en el Libro de Moisés4. En esta Perspectiva, describimos este hallazgo con más detalle.

Una correspondencia notable

En la historia de José Smith sobre Enoc, Mahíjah aparece de la nada, como el único personaje mencionado en el relato además del propio Enoc:

Y vino a él un hombre llamado Mahíjah, y le dijo: Dinos claramente quién eres, y de dónde vienes. Moisés 6:40

Más adelante en el relato, aparece el nombre similar “Mahújah”5 . Curiosamente, en el texto hebreo masorético de la Biblia, las variantes de nombre MḤYY'L (= Mahijael, con el sufijo “-el” que representa el nombre de Dios) y MḤWY'L (= Mehujael) aparecen en un solo versículo de la Biblia del rey Santiago como referencias a la misma persona6.

De forma significativa, debido a que la versión del rey Santiago traduce ambas variantes del nombre hebreo de manera idéntica en inglés, José Smith habría tenido que acceder e interpretar el texto hebreo para ver que había dos versiones del nombre, similares a las dos versiones que se encuentran en el Libro de Moisés. Pero no hay evidencia de que él o cualquier otra persona relacionada con la traducción de Moisés 6–7 supiera leer hebreo en ese momento o, de hecho, incluso tuviera acceso a una Biblia hebrea7.

Debe observarse que José Smith era muy consciente de que el libro bíblico de Judas cita explícitamente a Enoc8, aunque no demostrara ningún conocimiento de 1 Enoc, la fuente que Judas estaba citando. Si realmente hubiera estado buscando formas de reforzar el caso de la autenticidad de su traducción de la Biblia, lo más obvio que podría haber hecho hubiera sido incluir los versículos relevantes de Judas en algún lugar de su relato de Enoc. Pero el Profeta no lo hizo.

¿Los nombres “Mahaway”, “Mahújah” y “Mahíjah” fueron simplemente copiados de la Biblia?

Una posible explicación histórica de la similitud de los nombres del Libro de Moisés y el Libro de los Gigantes es que José Smith y el autor de Qumrán crearon de forma independiente nombres muy similares para un personaje importante en sus respectivos relatos. Uno podría preguntarse: ¿Qué posibilidades hay de que se les ocurrieran estos nombres tan parecidos de forma independiente?

Incluso si, por un momento, admitiéramos la hipótesis de que José Smith creó el nombre directa o indirectamente a través de su conocimiento de Génesis 4:18, ¿por qué eligió este nombre para su relato en lugar de algún otro? Si fuera una elección arbitraria, ¿por qué no eligió a Irad o Metusael o al aún más prominente Lamec del mismo versículo, o algún otro nombre de los versículos circundantes en su lugar? ¿Por qué Mahújah es el único personaje nombrado en los capítulos de Enoc del Libro de Moisés, aparte del propio Enoc, y también el único otro nombre plausiblemente relacionado con la Biblia, además de Enoc, en el Libro de los Gigantes?

Yendo más allá, uno de los paralelismos más importantes en los nombres del Libro de los Gigantes y del Libro de Moisés es que, en contraste con el nombre bíblico, ambos carecen del elemento teofórico (-el). Si José Smith obtuvo los nombres “Mahújah” y “Mahíjah” adaptándolos de Génesis 4:18, ¿por qué no habría, en aras de la coherencia, eliminado el sufijo “-el” en su traducción del propio versículo bíblico? Y si, en cambio, estuviera tratando deliberadamente de crear un nombre nuevo y distintivo con la terminación teofórica “-jah”, ¿qué propósito suficientemente importante habría cumplido para que se tomara esa molestia?

Además, dado que el autor del Libro de los Gigantes aparentemente no estaba completamente vinculado a la tradición escrita y tenía la libertad de incluir nombres no comprobados en otros lugares, como 'Ohyah y Hahyah para facilitar el juego de palabras, como algunos han sugerido, ¿por qué no habría inventado un nombre que fuera más similar a los otros dos en lugar del nombre más distintivo: Mahaway?9. ¿Y por qué José Smith, quien a veces ha suscitado críticas por los muchos nombres nuevos que se han incluido en sus traducciones de las Escrituras, se ha mostrado reacio a “inventar” solo uno más?

En cambio, ambos autores, sin una explicación viable del motivo, son vistos supuestamente como creadores de un nombre que es coincidentemente muy similar al que se encuentra en el mismo versículo bíblico, y luego usan estos nombres modificados para servir como apodo para un actor prominente que casualmente juega un papel análogo dentro de dos relatos independientes del profeta Enoc.

Explicación de Salvatore Cirillo sobre el origen de los nombres

Algunos no miembros de la Iglesia se han dado cuenta de la sorprendente naturaleza del parecido de estos nombres prominentes en el Libro de Moisés y el Libro de los Gigantes. Por ejemplo, en su tesis de maestría en la Universidad de Durham, Salvatore Cirillo, basándose en las conclusiones similares del conocido erudito del Libro de los Gigantes Loren Stuckenbruck10, considera que los nombres de los gibborim, entre los que se encuentra especialmente Mahaway, son “el contenido más notablemente independiente” en el Libro de los Gigantes, siendo “incomparable en otra literatura judía”. Además, según Cirillo, “el nombre Mahawai en el Libro de los Gigantes y los nombres Mahújah y Mahíjah en el Libro de Moisés representan la mayor similitud entre las revelaciones de los Santos de los Últimos Días sobre Enoc y los libros seudoepígrafos de Enoc (específicamente el Libro de los Gigantes)”11. Argumentando en términos contundentes que José Smith debió haber sabido sobre el Libro de los Gigantes mientras preparaba el relato de Enoc del Libro de Moisés, Cirillo escribe12:

La propia afirmación de Nibley de que Mahújah y Mahíjah del Libro de Moisés comparten su nombre con Mahaway en el Libro de los Gigantes es una prueba más de que la influencia de los libros seudoepígrafos de Enoc existió en los escritos de José Smith sobre Enoc13.

Lo que de forma manifiesta no se menciona en los argumentos de Cirillo sobre la influencia del texto arameo de Enoc en Moisés 6–7 es que, aparte de 1 Enoc, ninguno de los manuscritos judíos importantes de Enoc estaba disponible en una traducción al inglés durante la vida de José Smith. Es desconcertante que los argumentos más fuertes de Cirillo de que el Profeta haya sido influenciado por los antiguos seudoepígrafos de Enoc provengan del Libro de los Gigantes de Qumrán, ¡una obra que no fue descubierta hasta 1948! Cirillo no intenta explicar cómo un manuscrito que se desconocía hasta mediados del siglo XX pudo haber influido en el relato de Enoc en el Libro de Moisés, escrito en 1830.

Explicación de Matthew Black sobre el origen de los nombres

El único intento conocido de explicar cómo un manuscrito descubierto en 1948 pudo haber influido en la traducción de José Smith del Libro de Moisés en 1830 proviene de los recuerdos de dos personas sobre el conocido erudito arameo Matthew Black, quien colaboró con Józef Milik en la primera traducción al inglés de los fragmentos del Libro de los Gigantes en 1976. Black ciertamente sabía lo suficiente sobre el hebreo y el arameo antiguos como para haber reconocido si los nombres del Libro de Moisés: Mahújah y Mahíjah eran equivalentes aceptables en inglés de “Mahaway” del Libro de los Gigantes.

El candidato a doctorado Gordon C. Thomasson se acercó a Black después de una conferencia en la Universidad de Cornell, durante el año que Black pasó en el Instituto de Estudios Avanzados de Princeton (1977-1978)14. Según el relato de Thomasson15:

Le pregunté al profesor Black si estaba familiarizado con el texto de Enoc de José Smith. Dijo que no lo conocía pero que estaba interesado. Primero preguntó si era idéntico o similar a 1 Enoc. Le dije que no lo era y luego procedí a enumerar algunas de las correlaciones que el Dr. [Hugh] Nibley había mostrado con los materiales de Qumrán y Enoc etíope de Milik, Black y de otros. Se quedó callado. Cuando llegué a Mahújah16, levantó la mano en un gesto de “por favor, haz una pausa” y se quedó en silencio.

Finalmente, reconoció que el nombre Mahújah no podría provenir de 1 Enoc. Luego formuló una hipótesis, coherente con su conferencia, según la cual un miembro de uno de los grupos esotéricos que había descrito anteriormente [es decir, grupos clandestinos que habían mantenido, sub rosa, una tradición religiosa basada en los escritos de Enoc anteriores al Génesis] debe haber sobrevivido hasta el siglo XIX y, al oír hablar de José Smith, debe haber traído los textos de Enoc del grupo a Nueva York desde Italia para que el Profeta los tradujera y publicara.

Al final de nuestra conversación, expresó interés por ver más obras de Hugh. Le propuse a Black que se reuniera con Hugh, le di la información de contacto, [y él] se comunicó con Hugh el mismo día, como Hugh me confirmó más tarde. Pronto, Black hizo un viaje no planeado a Provo, donde se reunió con Hugh durante algún tiempo. Black también dio una conferencia pública como invitado, pero, según me dijeron, en ese foro público no se contestarían preguntas sobre Moisés.

Hugh Nibley grabó una conversación con Matthew Black que aparentemente ocurrió cerca del final de su visita a la BYU en 1977. Nibley le preguntó a Black si tenía una explicación para la aparición del nombre Mahújah en el Libro de Moisés, e informó su respuesta de la siguiente manera: “Bueno, algún día descubriremos la fuente que usó José Smith”17.

Una explicación más satisfactoria del origen de los nombres

Durante los años transcurridos, no ha surgido ninguna evidencia documental que confirme la hipótesis infundada de Black de que José Smith obtuvo de algún modo acceso a un manuscrito de Enoc como el Libro de los Gigantes gracias a un grupo religioso esotérico en Europa. Por otro lado, durante este mismo lapso de tiempo, ha surgido mucha evidencia adicional que vincula la revelación de José Smith sobre Enoc con una variedad de tradiciones textuales antiguas relevantes, en particular muchas del Libro de los Gigantes18. El paralelismo Mahíjah/Mahújah es solo una de las muchas conexiones antiguas para las que no existe una explicación histórica completamente satisfactoria. En nuestra opinión, la idea de que estas correspondencias hayan surgido por coincidencia o por medio de préstamos y alteraciones no es convincente. Por el contrario, estamos convencidos de que se deben a una antigua tradición común anterior a ambos textos, como Matthew Black aparentemente se sintió obligado a creer19.

En contraste con la idea de que el Libro de los Gigantes depende casi exclusivamente de la Biblia y 1 Enoc, la erudición actual ve indicios de raíces más antiguas y complejas para el texto de lo que alguna vez se reconoció. Por ejemplo, André Caquot, entre otros estudiosos, ha argumentado que “la referencia a Gilgamesh defiende el original del Libro de los Gigantes en una diáspora oriental”20.

De acuerdo con esta idea, Nahum Sarna21 y Richard Hess22, siguiendo a Umberto Cassuto23, sugieren que el nombre Mahaway podría explicarse a partir del acadio maḫḫû, que denota “una cierta clase de sacerdotes y videntes”24. ¿Y cuál era el papel de estos videntes? Entre otras cosas, los archivos reales del antiguo reino babilónico de Mari relatan las idas y venidas de los maḫḫû [extáticos o videntes] como intermediarios y mensajeros, portadores de palabras de advertencia de los dioses para el rey25, un papel que podría ser similar al de Mahaway.

El argumento de Cassuto sobre el origen del nombre se ve reforzado por la concordancia que encuentra en la palabra maḫḫû subyacente de Mehujael, el nombre del hijo de Mehujael, Metusael (un nombre que es “análogo no solo en forma sino también en significado”26), y el nombre del nieto de Mehujael, Lamec, que Cassuto considera que probablemente proviene de la palabra mesopotámica lumakku, que también significa una cierta clase de sacerdotes27. De forma importante, Hess informa que si bien la raíz lmk es desconocida en el semítico occidental, se encuentra tanto en los nombres personales del tercer milenio a. C. como en los nombres de Mari en la antigua Babilonia a principios del segundo milenio a. C.28.

En resumen, aunque todavía pueden encontrarse otras posibilidades, los estudiosos ya han identificado lo que parece ser una opción atractiva de una raíz acadia común subyacente a los nombres similares en la Biblia, el Libro de los Gigantes y el Libro de Moisés. A la luz de tal sugerencia, ¿es posible que Mehujael, Mahaway, Mahújah y Mahíjah deriven de manera independiente de la misma raíz o de una similar, habiendo llegado al autor a través de tradiciones extracanónicas en lugar de haber simplemente sido tomados de la Biblia? Por el momento, no vemos ninguna razón para descartar esta hipótesis plausible.

Conclusión: Nombres antiguos restaurados a través de la Revelación

Después de revisar las evidencias, es comprensible que los lectores se pregunten si los nombres “Mahújah” y “Mahíjah” fueron simplemente tomados de la Biblia y adaptados. Esta hipótesis hace que sea difícil explicar los paralelismos sorprendentemente específicos entre estos nombres en el Libro de Moisés y el nombre "Mahaway" del Libro de los Gigantes.

¿José Smith podría haber tenido conocimiento de los nombres a través de un manuscrito arameo desconocido del Libro de los Gigantes traducido al inglés y puesto secretamente a su disposición antes de que los investigadores de Qumrán lo descubrieran en 1948? ¿Los nombres fueron transferidos de alguna manera a José Smith a través de un grupo esotérico desconocido, como propuso el profesor Black? Una vez más, las explicaciones puramente históricas defraudan. Tales propuestas se basan puramente en especulaciones y no pueden proporcionar respuestas sobre la identidad de estos supuestos colaboradores, cómo se encontraron con tal manuscrito, por qué lo tradujeron en secreto al inglés y lo pusieron a disposición de José Smith y cómo el Profeta ocultó este fraude de sus colaboradores o los persuadió para que se confabularan con él. A medida que la cadena de conjeturas requeridas crece, su probabilidad creciente disminuye.

Una conclusión más convincente, en nuestra opinión, es que estos nombres, junto con otras evidencias de la antigüedad en el relato de Enoc del Libro de Moisés, fueron restaurados directamente del mundo antiguo a través del proceso de la revelación divina.

Este artículo fue adaptado a partir de Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Matthew L. Bowen y Ryan Dahle. "Where did the names 'Mahaway' and 'Mahujah' come from? A response to Colby Townsend’s 'Returning to the Sources'”, Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (2020): presentado para su revisión.

Otras lecturas

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. y David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. En God's Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation y Eborn Books, 2014, págs. 42–45, 69, 128.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. y Ryan Dahle. “Could Joseph Smith have drawn on ancient manuscripts when he translated the story of Enoch? Recent updates on a persistent question (4 October 2019)”. Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 33 (2019): 305–373. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/could-joseph-smith-have-drawn-on-ancient-manuscripts-when-he-translated-the-story-of-enoch-recent-updates-on-a-persistent-question/. (consultado el 23 de octubre de 2019), págs. 312–319.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Matthew L. Bowen y Ryan Dahle. “Where did the names ‘Mahaway’ and ‘Mahujah’ come from?: A response to Colby Townsend’s ‘Returning to the sources’”. Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (2020): presentado para su revisión.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown y Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, págs. 96, 112.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, págs. 277–279.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, págs. 268–269.

———. 1992. Hugh Nibley on the Book of Enoch. Video de YouTube de FairMormon, con una descripción de la visita de Matthew Black a BYU aproximadamente en los minutos 6:04–6:50 en el video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3PvM-4T7dU.

Consultas

al-Tabari. d. 923. The History of al-Tabari: General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood. Vol. 1. Traducido por Franz Rosenthal. Biblioteca Persica, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1989.

al-Tha'labi, Abu Ishaq Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim. d. 1035. 'Ara'is Al-Majalis Fi Qisas Al-Anbiya' o "Lives of the Prophets". Traducido por William M. Brinner. Studies in Arabic Literature, Supplements to the Journal of Arabic Literature, Volume 24, ed. Suzanne Pinckney Stetkevych. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Bandstra, Barry L. Genesis 1-11: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text. Baylor Handbook on the Hebrew Bible, ed. W. Dennis Tucker, Jr. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2008.

Black, Jeremy, Andrew George y Nicholas Postgate, eds. A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian Second ed. Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2000. https://books.google.com/books?id=-qIuVCsRb98C. (consultado el 19 de mayo de 2020).

Davis Bledsoe, Amanda M. "Throne theophanies, dream visions, and righetous(?) seers". En Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions and Influences, editado por Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck y Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 81-96. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Bowen, Matthew L. Mensaje de correo electrónico a Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, 18 de marzo de 2020.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. y David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. En God's Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation y Eborn Books, 2014. www.templethemes.net.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Matthew L. Bowen y Ryan Dahle. “Where did the names 'Mahaway' and 'Mahujah' come from?: A response to Colby Townsend’s 'Returning to the sources'”. Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (2020): presentado para su revisión.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. y Ryan Dahle. "Textual criticism and the Book of Moses: A response to Colby Townsend’s 'Returning to the sources'". Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (2020): en proceso de impresión www.templethemes.net.

Brenton, Lancelot C. L. 1851. The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Calabro, David. Mensaje de correo electrónico a Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, 24 de enero de 2018.

Caquot, André. "Les prodromes du déluge: légendes araméenes du Qoumrân". Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses 83, no. 1 (2003): 41-59. https://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/rhpr_0035-2403_2003_num_83_1_1011.pdf. (consultado el 11 de abril de 2020).

Cassuto, Umberto. 1944. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 1: From Adam to Noah. Traducido por Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1998.

Cirillo, Salvatore. "Joseph Smith, Mormonism, and Enochic Tradition". Tesis de Maestría, Durham University, 2010.

Clarke, Adam. The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments. New York City, NY: N. Bangs y J. Emory, for the Methodist Eposcopal Church, 1825. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Holy_Bible_Containing_the_Old_and_Ne.html?id=Lds8AAAAYAAJ. (consultado el 19 de febrero de 2020).

Dogniez, Cécile y Marguerite Harl, eds. Le Pentateuque d'Alexandrie: Texte Grec et Traduction. La Bible des Septante, ed. Cécile Dogniez y Marguerite Harl. Paris, Francia: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2001.

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson y Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith's New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

George, Andrew, ed. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. London, England: The Penguin Group, 2003.

Goff, Matthew. "Gilgamesh the Giant: The Qumran Book of Giants’ appropriateion of Gilgamesh motifs". Dead Sea Discoveries 16, no. 2 (2009): 221-53.

Halloran, J. A. Sumerian Lexicon: A Dictionary Guide to the Ancient Sumerian Language. Los Angeles, CA: Logogram Publishing, 2006. https://www.sumerian.org/sumerlex.htm. (consultado el 20 de mayo de 2020).

Heimpel, Wolfgang. Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2003.

Hendel, Ronald S. The Text of Genesis 1-11: Textual Studies and Critical Edition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Hess, Richard S. Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1-11. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. "El Libro de los Gigantes (4Q203)". En The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, editado por Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2a. ed. Traducido por Wilfred G. E. Watson. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

McKane, William. 1994. Matthew Black. En Obituaries of Past Fellows, Royal Society of Edinburgh. http://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/obits_alpha/black_matthew.pdf. (consultado el 3 de abril de 2013).

Milik, Józef Tadeusz y Matthew Black, eds. The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments from Qumran Cave 4. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Nibley, Hugh W. "Churches in the wilderness". En Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless, editado por Truman G. Madsen, 155-212. Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1978.

———. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. 1992. Hugh Nibley on the Book of Enoch. Extraído de un videocasete de FARMS titulado "The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Era Dawns". El videocasete contiene material grabado en relación con una Conferencia Nacional Interreligiosa sobre los Rollos del Mar Muerto, el 20 de noviembre de 1992 en el Auditorio Kresge de la Universidad de Stanford. En FairMormon Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3PvM-4T7dU. (consultado el 20 de mayo de 2020).

———. "Letter to Frederick M. Huchel". Provo, UT: L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Boyd Jay Petersen Collection, MSS 7449, Box 3, Folder 3, May 6, 1997.

———. 1978. "Churches in the wilderness". En The Prophetic Book of Mormon, editado por John W. Welch. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 8, 289-327. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Oppenheim, A. Leo. 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Ed. revisada Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Peters, Melvin K. H., ed. A New English Translation of the Septuagint and the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included under that Title: Deuteronomy Edición provisional. NETS: New English Translation of the Septuagint, ed. Albert Pietersma y Benjamin Wright. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004. http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/nets/edition/deut.pdf.

Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore en Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions. Monographs of the Hebrew Union College 14. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Shoulson, Mark, ed. The Torah: Jewish and Samaritan Versions Compared: LightningSource, 2008.

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Andrew F. Ehat y Lyndon W. Cook. The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph, 1980. https://rsc-legacy.byu.edu/out-print/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph. (consultado el 25 de abril de 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1805-1844. The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin y Richard Lyman Bushman. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian's Press, 2008-. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org.

———. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. The Book of Giants from Qumran: Texts, Translation, and Commentary. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Thomasson, Gordon C. "Items on Enoch — Some Notes of Personal History. Expansion of remarks given at the Conference on Enoch and the Temple, Academy for Temple Studies, Provo, Utah, 22 February 2013 (manuscrito inédito, 25 de febrero de 2013)". 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EaRw40r-TfM.

———. "Email message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw". April 7, 2014.

Tsedaka, Benyamim y Sharon Sullivan, eds. The Israelite Samaritan Version of the Torah. Traducido por Benyamim Tsedaka. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2013.

Weber, Robert, ed. Biblia Sacra Vulgata 4th ed: American Bible Society, 1990.

Wevers, John William. Notes on the Greek Text of Genesis. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993.

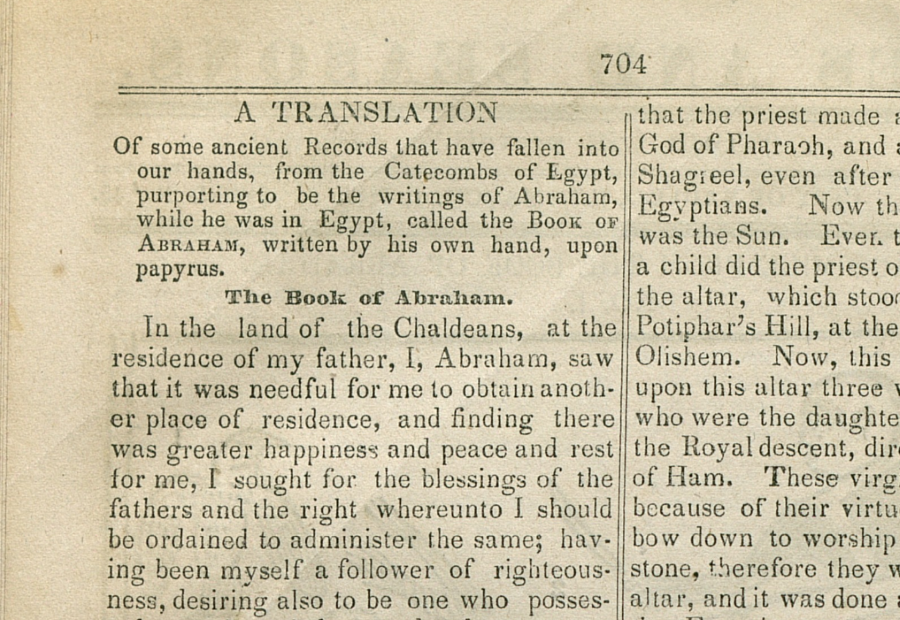

Notas sobre las Ilustraciones

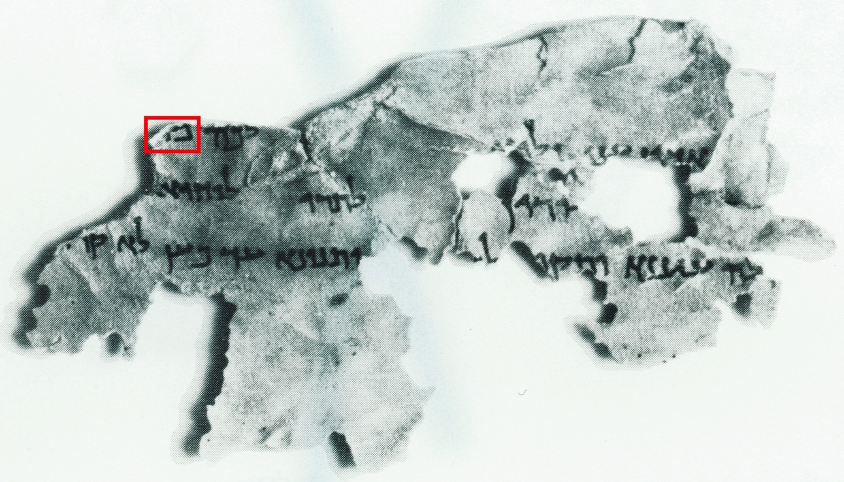

Ilustración 1. Fotografía de 4QEn Giantsa [4Q203], Fragmento 7, columna ii de la Lámina 31, J. T. Milik et al., Enoch, con autorización. A diferencia de muchos de los otros fragmentos arameos mal conservados del Libro de los Gigantes, la traducción de este es clara: “(5) […] a ti, Mah[awai…] (6) las dos tablas […] (7) y la segunda no se ha leído hasta ahora [… ].” Aunque la “Ḥ” es difícil de ver en la fotografía del manuscrito que hemos reproducido aquí, F. G. Martínez, Libro de los Gigantes (4Q203), Fragmento 7, columna ii, líneas 5-7, pág. 260, interpreta el final de la línea 5 como “MḤ”. Milik también ve una “MḤ” en la línea 5 y lo interpreta como la primera parte del nombre MḤWY (J. T. Milik et al., Enoch, pág. 314). Por el contrario, L. T. Stuckenbruck, Libro de los Gigantes, pág. 84 y J. C. Reeves, Jewish Lore, pág. 110 ven solo “M” y no “MḤ” en este fragmento en particular. Aunque solo la primera o las dos primeras letras del nombre MḤWY se conservan en el Fragmento 7 de 4Q203, el nombre completo Mahawai/Mahújah aparece en otros fragmentos más completos del Libro de los Gigantes (por ejemplo, 4Q530, 7 ii). En las traducciones al inglés del Libro de los Gigantes, el nombre suele transcribirse como “Mahaway” o “Mahawai”, pero en el Libro de Moisés aparece como “Mahíjah” (Moisés 6:40) o “Mahújah” (7:2).

Ilustración 2. National Portrait Gallery, Londres. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp77746/matthew-black (consultado el 16 de septiembre de 2019).

1 H. W. Nibley, Enoch, pág. 276. Cf. Ibíd., págs. 267-268.

2 Publicado como J. T. Milik et al., Enoch.

3 Obsérvese que las vocales en la transliteración inglesa del nombre MHWY del Libro de los Gigantes son en gran medida una cuestión de conjeturas, ya que no aparecen vocales en el texto arameo. Por otro lado, con respecto a Mahújah (MHWY/MḤWY) y Mahíjah (MHYY/MḤYY) del Libro de Moisés, tenemos versiones en inglés de los nombres que contienen vocales, pero es imposible decir a partir del texto en inglés solamente si la segunda consonante en los nombres se habría escrito antiguamente como el equivalente de una “H” (como en el Libro de los Gigantes) o una Ḥ (como en Génesis 4:18).

Con respecto al nombre similar de la Biblia del rey Santiago, Mehujael, mencionado dos veces en Génesis 4:18, el hebreo subyacente se escribe de manera diferente en cada caso, es decir, tanto Mehujael (MḤWY-EL) como Mehijael (MḤYY-EL). La presencia de variantes ortográficas del nombre (“u” vs. “i”) es intrigante en vista de los nombres del Libro de Moisés con variantes vocales similares (Mahújah vs. Mahíjah). Por un lado, los nombres del Libro de Moisés se asemejan a las dos versiones hebreas del nombre en Génesis 4:18 ya que se presentan tanto la variante “ú” como la “í” del nombre. Por otro lado, los nombres del Libro de Moisés son similares al nombre del Libro de los Gigantes en el sentido de que omiten la terminación teofórica “-EL” de Génesis 4:18, un nombre para Dios.

Los nombres del Libro de Moisés terminan con una “h” en su ortografía en inglés. Esto los hace diferentes de los nombres de Génesis 4:18 y del Libro de los Gigantes. Es imposible saber solo a partir de la evidencia del manuscrito si la terminación “-jah” de los nombres del Libro de Moisés tenía la intención de representar el nombre del Dios de Israel (Salmo 68:4), o si la “h” al final de la versión en inglés del nombre está presente por alguna otra razón. Por ejemplo, dada la prevalencia de las terminaciones “-jah” en los nombres [en inglés] del Antiguo Testamento (p. ej., Elijah [Elías]), no es de extrañar que un escriba de habla inglesa que oyera la pronunciación del nombre de Génesis en la TJS durante el proceso de dictado pudiera haber escrito el nombre con una “h” al final para que la ortografía se ajustara a esta convención de denominación común.

Para agravar la dificultad de quienes no son especialistas a la hora de reconocer similitudes y diferencias en la ortografía de los nombres antiguos, los traductores difieren en sus convenciones de transliteración al inglés. Por ejemplo, las letras inglesas “j”, “y” e “i” se utilizan de diversas formas para representar la letra semítica yod. Por lo tanto, en las traducciones al inglés del Libro de los Gigantes, vemos varias variantes del mismo nombre: Mahaway (la más común), Mahawai, Mahway y Mahuy, o, con la “y” transliterada con una “j” como se hace frecuentemente con otros nombres que contienen una yod en la Biblia del rey Santiago, Mahuj.

Como en todos los idiomas, la forma y la ortografía de los nombres también cambian con el tiempo y a medida que pasan de una cultura a otra. En J. M. Bradshaw et al., Where Did the Names “Mahaway” and “Mahujah” Come From? se argumenta que a pesar de una diferencia significativa en una consonante (“Ḥ” [de la Biblia] contra “H” [del Libro de los Gigantes]), actualmente no existe una razón convincente por la cual el nombre MHWY en el Libro de los Gigantes (con toda la variedad de sus equivalentes en inglés) no pudiera haber estado relacionado en algún momento de su historia con los elementos del nombre de la Biblia del rey Santiago Mehuja-/Mehija- (escrito como MḤWY-/MḤYY-) y con los nombres del Libro de Moisés Mahújah (MHWY/MḤWY) y Mahíjah (MHYY/MḤYY).

4 H. W. Nibley, Enoch, págs. 277–279; H. W. Nibley, Churches, págs. 156-159; H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, págs. 267–269. Al evaluar las sugerencias de Nibley, el erudito SUD David Calabro observa que Nibley, aunque brillante, era más un filólogo que un lingüista, “y como tal, generalmente no se enfocaba en exponer los detalles de las conexiones lingüísticas. También trataba las conexiones a un nivel literario generalizado, dando por sentado que las palabras y los nombres a veces se confunden en la transmisión” (D. Calabro, January 24 2018).

Si bien mantiene la posibilidad de una correspondencia entre el equivalente antiguo de estos nombres, Calabro explica por qué no podemos plantear una equivalencia directa entre todos ellos (incluidos los nombres relacionados Mahujael/Mahijael en Génesis 4:18) en sus formas actuales (ibíd.):

El -ah en Mahújah y Mahíjah es problemático si se interpretan las formas actuales de estos nombres como equivalentes de Mahawai y también de Mehuja-/Mehija- en Mehujael/Mahijael al mismo tiempo. En otras palabras, Mahújah puede ser = MHWY + Jah o Mehjael puede ser = Mahujael puede ser = Mahujah + El, pero ambas ecuaciones no pueden aplicarse a las formas actuales de estos nombres al mismo tiempo.

Por supuesto, observa Calabro, las reglas eran diferentes en épocas anteriores, ya que “la supresión de las vocales finales solo se produjo en algún momento entre 1200 y 600 a. C.” (ibíd.):

Pero es poco probable que los nombres de Moisés prueben algo de esto. José dejó intactos el resto de los nombres bíblicos. Y si Lehi, Pablo y Judas tuvieron acceso al Libro de Moisés (como creo que pasó), el nombre habría eliminado cualquier vocal corta final antes de que el texto terminara de transmitirse.

Dicho esto, Calabro continúa explicando por qué las conexiones entre estos nombres no son improbables, incluso frente a estas consideraciones (ibíd.):

Muy a menudo, en las tradiciones seudoepigráficas, se encuentran nombres que suenan similares (o, a veces, ni siquiera similares), solo un poco confusos. Es frecuente en las formas árabes de los nombres bíblicos: Ibrahim para “Abraham” (quizás influenciado por Elohim o algún otro sustantivo hebreo plural), 'Isa por Yasu' “Jesús”, etc. Así que Mahújah, Mahíjah, Mehujael/Mehijael y MḤWY podrían estar todos relacionados, con algo que se mezcló en la transmisión.

Con respecto a las correspondencias entre Mahújah y Mahíjah, Nibley (H. W. Nibley, Enoch, pág. 278; H. W. Nibley, Churches, pág. 157) sostiene que son variantes del mismo nombre, dado que “Mehuja-el” aparece en la Septuaginta como “Mai-el” (C. Dogniez et al., Pentateuque, Genesis 4:18, pág. 145; M. K. H. Peters, Deuteronomy, Genesis 4:18, pág. 8) y en la Vulgata latina como Mawiah-el ( R. Weber, Vulgata, Genesis 4:18, pág. 9). Dado que la versión griega no tenía una “Ḥ” interna, Nibley considera que “Mai-” solo podía provenir de “Mahi-” (MḤY-).

J. W. Wevers también escribe que la ortografía de la Septuaginta de Mai-el [en Génesis 4:18] “sigue la tradición samaritana de [Mahi-el]” (J. W. Wevers, Notes, pág. 62 n. 4:18) siendo la única diferencia la “h” suprimida. Según Nibley, la versión de Mahawai que vemos en el Libro de los Gigantes está probablemente relacionada con Génesis 4:18. Aparece en la Vulgata latina como “Maviahel” probablemente debido al hecho de que Jerónimo tomó la versión hebrea para su traducción. Tampoco usó la “Ḥ” e hizo de la “W” una consonante (“v”) en lugar de una vocal (“u”) en su transliteración. Es por eso que en la Biblia de Douay-Rheims (basada en la Vulgata), vemos el nombre traducido como “Maviael”. Véase más información sobre Génesis 4:18 a continuación.

Tenga en cuenta que el abuelo del profeta Enoc también llevaba un nombre similar a Mahawai/Mahújah: Mahalaleel (Génesis 5:12-17; 1 Crónicas 1:2; Moisés 6:19-20. Véase también Nehemías 11:4). Como testimonio de la facilidad con la que pueden confundirse esos nombres, obsérvese que el manuscrito griego utilizado para la traducción de Brenton de la Septuaginta se lee “Maleleel” en lugar de “Maiel” en Génesis 4:18 (L. C. L. Brenton, Septuaginta, Genesis 4:18, pág. 5).

5 Moisés 7:2. Se ha argumentado que la presencia de dos nombres similares, “Mahíjah y Mahújah”, en el Libro de Moisés se debe a un error de transcripción. En J. M. Bradshaw et al., Textual Criticism se argumenta que la evidencia de tal error es cuestionable.

Tenga en cuenta que Mahújah puede leerse como el nombre de un lugar o como un nombre personal. En la versión canónica de 2013 del Libro de Moisés, Moisés 7:2 dice: “Mientras viajaba y me hallaba en el lugar llamado Mahújah, clamé al Señor, y vino una voz de los cielos que decía: Vuélvete y asciende al monte de Simeón”.

Sobre la base del pronombre [en inglés] “I” que está presente en el manuscrito OT1 (véase S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, pág. 103) y el uso de la segunda persona del plural [en inglés] “ye” (vosotros) que aparece dos veces más adelante en el versículo. Cirillo defiende una lectura alternativa: “As I was journeying and stood in the place, Mahujah and I cried unto the Lord. There came a voice out of heaven, saying—Turn ye, and get ye upon the mount Simeon” [Mientras viajaba y estaba en el lugar, Mahújah y yo clamamos al Señor. Vino una voz del cielo que decía: Volveos y subid al monte Simeón] (S. Cirillo, Joseph Smith., pág. 103, puntuación modificada). Esta interpretación convierte el nombre Mahújah en un nombre personal en lugar de un nombre de lugar, es decir, con el significado de que Enoc “está con” Mahújah, “no en Mahújah” (ibíd., pág. 103). Un problema con esta interpretación es que después, Enoc subió a encontrarse con Dios (“me volví y subí al monte;… y mientras estaba en el monte” [Moisés 7:3]). La única manera de compaginar la ausencia de Mahújah en acontecimientos subsecuentes sería que no siguiera a Enoc al monte como se le había ordenado que hiciera en Moisés 7:2 (tomando la oración [en inglés] “Turn ye” [volveos] en plural).

Por otro lado, en una interpretación diferente, David Calabro señala que Moisés 7:2 “As I was journeying … and I cried” [Mientras viajaba… y clamé] “podría ser un ejemplo del uso de 'and' para introducir una cláusula principal después de una cláusula circunstancial, que es un hebraísmo que se encuentra con frecuencia en el texto más antiguo del Libro de Mormón” (D. Calabro, January 24 2018). En este caso, “ye” [vosotros] en “Turn ye” [volveos] tendría que interpretarse como singular en lugar de plural.

Si de hecho el nombre del monte Mahújah, al que subió Enoc para orar, se relaciona con la idea de interrogar (como se propone en un comentario de Nibley más adelante), proporcionaría una clara contraparte del nombre del monte Simeón (hebreo Shi'mon = ha oído), a donde se le ordenó a Enoc que fuera para recibir sus respuestas. Obsérvese el relato de Al-Tha'labi sobre el reencuentro de Adán y Eva después de su separación cuando “se reconocieron el uno al otro al interrogarse en un día de cuestionamientos. Así que el lugar se llamó 'Arafat (= preguntas) y el día: 'Irfah”. (A. I. A. I. M. I. I. al-Tha'labi, Lives, pág. 54; cf. al-Tabari, Creation, 1:120, pág. 291).

6 El uso de dos variantes del mismo nombre en un mismo enunciado no es inusual en la Biblia hebrea. En este caso, el texto masorético de Génesis 4:18 incluye ambas grafías del nombre (Mehuja-el y Mehija-el) una tras otra, y en un contexto que no deja lugar a dudas de que las dos ocurrencias se refieren al mismo individuo (véase, por ejemplo, B. L. Bandstra, Genesis 1-11, pág. 268; ibíd., pág. 268; ibíd., pág. 268). R. S. Hendel, Text, págs. 47-48; ibíd., págs. 47-48; ibíd., págs. 47-48 atribuye este fenómeno, bien a una confusión gráfica de “Y” y “W” (cf. H. W. Nibley, Enoch, pág. 278; H. W. Nibley, Churches (1989), págs. 289-290) o bien a la modernización lingüística de lo que parece ser la forma más antigua (Mehuja-el). Nótese que en lugar de presentar dos formas diferentes del nombre en sucesión como en el texto masorético, algunos otros textos presentan los nombres de manera consistente. Por ejemplo, el manuscrito Geniza de El Cairo presenta dos veces Mehuja-el, mientras que la versión samaritana tiene Mahi-el (cf. Mehijael) dos veces (M. Shoulson, Torah, Genesis 4:18, pág. 11; B. Tsedaka et al., Israelite Samaritan, Genesis 4:18, pág. 12).

7 Como explicación alternativa para los dos nombres variantes en el Libro de Moisés, se ha argumentado que José Smith poseía y usó una copia del comentario bíblico de Adam Clarke de 1825 (A. Clarke, Holy Bible), que enumera las transliteraciones de las dos variantes hebreas de Mehujael en Génesis 4:18 en la página 151. Pero, por razones explicadas en detalle en J. M. Bradshaw et al., Where Did the Names “Mahaway” and “Mahujah” Come From?, esto parece poco probable.

Entre otras consideraciones, las pruebas de las traducciones de nombres por parte de José Smith en Génesis 4:18-19 ponen en duda la idea de que hubiera estado interesado en un escrutinio meticuloso de la tabla de variantes ortográficas de Clarke para obtener dos versiones del nombre Mehujael que pudiera alterar y usar en su relato de Enoc. En las pocas líneas que contienen su interpretación del nombre bíblico Mehujael, encontramos tres ejemplos de variantes ortográficas del nombre: Mehujael/Mahujael, Mathusael/ Mathusiel, Lameh/Lamec (S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, OT1 página 10, pág. 95). La evidencia proporcionada por estas variantes da la impresión de que la ortografía de estos nombres se basó simplemente en lo que los escribas escucharon leer a José Smith, más que en un esfuerzo por ajustarse a la Biblia o a otros documentos escritos para mantener la coherencia.

Independientemente de si José Smith hizo referencia o no a un comentario publicado como ayuda para la traducción durante las primeras fases de su trabajo en la Biblia, lo que debilita el argumento de que José Smith se basó en la tabla de Clarke en este caso es la falta de un argumento creíble de por qué el Profeta se habría sentido motivado a hacerlo. Los lectores tendrán que juzgar por sí mismos la probabilidad de que José Smith realmente hubiera tenido el tiempo, la paciencia y, lo más importante, una razón convincente para buscar en el comentario de Clarke dos nombres variantes que pudiera utilizar para un desconocido personaje mencionado dos veces en su traducción del Génesis, presumiblemente para darle más credibilidad. Hay que recordar que no dudó en publicar anteriormente decenas de nombres de aspecto extraño en el Libro de Mormón para los que no tenía una Biblia que lo respaldara.

8 Judas 1:14-15. Como prueba de que José Smith conocía estos versículos, véase esta observación en el prefacio de Moisés 7, el relato de la visión de Enoc, como parte de su historia (J. Smith, Jr., Documentary History, December 1830, 1:132. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Papers 2008-, History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], pág. 81, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/87 [consultado el 20 de mayo de 2020]):

El comentario común era que son “libros perdidos”; pero parece que la iglesia apostólica tenían algunos de estos escritos, tal como Judas menciona o cita la profecía de Enoc, la séptima generación desde Adán.

Aunque la porción de la historia de José Smith en la que aparece esta cita no fue compilada antes de enero de 1843, cuando William W. Phelps comenzó a ayudar a Willard Richards en esta tarea, José Smith “dictó o suministró información para gran parte de A-1” y estaba lo suficientemente familiarizado con el Nuevo Testamento como para hacer probable su conocimiento de estos versículos en Judas para diciembre de 1830 y enero de 1831, cuando se tradujo el relato de Enoc.

Nótese también que el Profeta citó un pasaje de la cita de Enoc sobre Judas (Judas 1:14) en una carta a los santos de Misuri escrita el 10 de diciembre de 1833 (J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 10 December 1833, pág. 36. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Papers 2008-, JS Letterbook 1, Letter to Edward Partridge and Others, 10 December 1833, pág. 72, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-edward-partridge-and-others-10-december-1833/4 [consultado el 20 de mayo de 2020]). Y utilizó Judas 1:14-15 en relación con sus enseñanzas sobre Enoc el 5 de octubre de 1840 (Véase J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 5 October 1840, pág. 170; J. Smith, Jr. et al., Words, discurso grabado de la mano de Robert B. Thompson, 5 October 1840, pág. 41; J. Smith, Jr., Papers 2008-, Instruction on Priesthood, 5 October 1840, pág. 6, https: // www. josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/instruction-on-priesthood-5-october-1840/11 [consultado el 20 de mayo de 2020]).

9 Parece posible que los nombres 'Ohyah y Hahyah fueran inventados por un juego de palabras basado en las formas hebreas de sus nombres. Sin embargo, para una descripción detallada de varias razones por las que el juego de palabras basado en una forma aramea de un verbo en el nombre Mahaway es poco probable, véase J. M. Bradshaw et al., Where Did the Names “Mahaway” and “Mahujah” Come From?

10 S. Cirillo, Joseph Smith., pág. 97. Cf. L. T. Stuckenbruck, Libro de los gigantes, pág. 27.

11 En esta cita y en otras posteriores de Cirillo, deletreamos los nombres de las obras que cita en lugar de utilizar versiones abreviadas de los nombres como lo hizo él.

12 S. Cirillo, Joseph Smith., pág. 126.

13 Cirillo continúa diciendo “Y una prueba adicional del conocimiento de Smith del [Libro de los Gigantes] se hace evidente por su uso del nombre en clave Baurak Ale”. Para obtener más información sobre Barak Ale/Baraq'el, consulte J. M. Bradshaw et al., God's Image 2, M6-19, págs. 96–97.

14 W. McKane, Matthew Black.

15 G. C. Thomasson, Items on Enoch — Some Notes of Personal History. Expansion of remarks given at the Conference on Enoch and the Temple, Academy for Temple Studies, Provo, Utah, 22 February 2013 (manuscrito inédito, 25 de febrero de 2013); G. C. Thomasson, April 7 2014.

16 Moisés 7:2.

17 H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, pág. 269. Para ver el relato completo, consulte las págs. 267–269. En otra parte, Nibley ofrece un relato similar (H. W. Nibley, Letter to Frederick M. Huchel):

En la semana en que apareció [la traducción de Milik y Black de los fragmentos arameos de Enoc] en 1976, pasé varios días con el Dr. Black. Estaba muy impresionado por ciertos paralelismos entre el Libro de Enoc de Qumrán y el de José Smith. Cuando comencé a pedirle explicaciones, cambiaba a otros temas. … Él es el presidente del St. Andrews Golf Club en Escocia, el más antiguo del mundo, y prefería hablar de golf con Billy Casper, que también estaba de visita aquí en ese momento, que discutir sobre el Libro de Enoc. Dijo varias veces, moviendo la cabeza de manera desconcertada: “Algún día descubriremos de dónde sacó eso José Smith. … Algún día aparecerá una fuente”. Lo cual no dudo ni un momento, puesto que ya tenemos una muestra impresionante. Me temo que no será lo que el hermano Black espera.

Véase también el extracto de video de una entrevista de Hugh Nibley grabada en relación con una Conferencia Nacional Interreligiosa sobre los Rollos del Mar Muerto, el 20 de noviembre de 1992 en el Auditorio Kresge de la Universidad de Stanford (H. W. Nibley, Hugh Nibley on the Book of Enoch). Los comentarios de Nibley sobre su encuentro con Black aparecen alrededor del minuto 6:04–6:50.

18 Véase "La misión de enseñanza de Enoc: ¿Los manuscritos antiguos de Enoc fueron la inspiración para Moisés 6–7?" Perspectiva del Libro de Moisés #5 (28 de octubre de 2020), para obtener una descripción general de estas conexiones.

19 En A. M. Bledsoe Davis, Throne Theophanies, pág. 85 se ofrece un argumento a favor de las tradiciones mesopotámicas comunes más antiguas dentro de Ezequiel 1, Daniel 7, 1 Enoc 14 y el Libro de los Gigantes Específicamente, ella argumenta que la adopción de 1 Enoc 14 de la idea estilo Daniel de la deidad muestra solo que esta idea fue “aceptada incluso en un período tardío, y no hace [a 1 Enoc 14] automáticamente más antiguo incluso si la tradición puede ser observada en escritos generalmente más antiguos”. En términos más generales, concluyó que “los tres textos se inspiraron en una tradición común (o tradiciones comunes) con respecto al trono celestial y luego lo adaptaron para que encajara en su contexto individual” (ibíd., pág. 90). En otras palabras (según Bledsoe-Davis), Daniel, 1 Enoc y el Libro de los Gigantes se basan de forma independiente en “una tradición común (o tradiciones comunes)” que es (son) más antigua(s) que cualquiera de los tres textos.

Con respecto específicamente a los orígenes de los nombres en el Libro de los Gigantes, el consenso académico reconoce que la aparición sorpresa de los nombres Gilgamesh y Ḥobabish en el Libro de los Gigantes se debe a influencias directas y/o indirectas de algún tipo de la epopeya acadia de Gilgamesh. (A. George, Gilgamesh). Milik fue el primero en notar la primera y “única mención de Gilgamesh fuera de la literatura cuneiforme”, así como en reconocer que el nombre Ḥobabish deriva de Humbaba, el monstruo asesinado por Gilgamesh (J. T. Milik et al., Enoch, pág. 313 n. L-6). Matthew Goff, entre otros, ha aclarado y ampliado la relación entre la epopeya de la Antigua Babilonia y el texto fragmentario arameo Enoc (M. Goff, Gilgamesh the Giant). Aunque algunos de los nombres del Libro de los Gigantes (por ejemplo, 'Ohyah, Hahyah) pueden ser invenciones ad hoc para facilitar el juego de palabras en el texto, se ha argumentado en otra parte que tal invención para ese propósito parece mucho menos plausible para el nombre Mahaway (J. M. Bradshaw et al., Where Did the Names “Mahaway” and “Mahujah” Come From?). Al igual que Gilgamesh, es más probable que Mahaway sea un nombre ya conocido en la tradición que uno creado ad hoc para el Libro de los Gigantes por un juego de palabras (como 'Ohyah y Hahyah).

20 A. Caquot, Les Prodromes, pág.50.

21 N. M. Sarna, Genesis, pág. 36.

22 R. S. Hess, Studies, pág. 41.

23 U. Cassuto, Adam to Noah, pág. 232.

24 Ibíd., pág. 232. Para obtener más información sobre su papel y función, consulte A. L. Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia, pág. 221. Cf. W. Heimpel, Letters to the King, pág. 578 s. v. extático.

25 Véase W. Heimpel, Letters to the King, 26 220, pág. 262 y 26 221, pág. 263.

26 U. Cassuto, Adam to Noah, pág. 233.

27 Ibíd., pág. 233. Cf. R. S. Hess, Studies, pág. 46.

28 R. S. Hess, Studies, pág. 46. Bowen comenta más sobre el análisis de Cassuto y otras posibles etimologías mesopotámicas para estos nombres de la siguiente manera (M. L. Bowen, 18 de marzo de 2020):

Metusael puede constituir o no una hebraización de la forma acadia ampliamente aceptada, pero aún (por ahora) teórica y no comprobada, mutu ša ili (“hombre de dios”). Sin embargo, Mesopotamia parece ser un buen lugar donde buscar para obtener etimologías más precisas para los nombres en las genealogías de Génesis.

Dado que Umberto Cassuto abre la puerta a considerar el acadio maḫḫû (“extático, profeta”, J. Black et al., Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, pág. 190) como la fuente del primer elemento en Mehujael, también podemos considerar la palabra maḫḫû (“gran”) como posible fuente. El último término deriva del sumerio MAḪ (adj. “alto[;] … exaltado, supremo, grande, excelso, principal, sublime, espléndido” J. A. Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon, pág. 168). Si Cassuto tiene razón en que Lamec puede estar relacionado con el acadio lumakku, hacemos bien en señalar que lumakku o lumaḫḫû (que también puede significar “jefe, gobernante”, J. Black et al., Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, pág. 185) también parece derivar del sumerio MAḪ (LÚ.MAḪ = “gran hombre”). Esto puede tener más relación con la etimología del nombre del Libro de Moisés “Mahán” en Moisés 5:31, 49 [escrito “Mahon” en la Traducción de José Smith OT1, pág. 10, S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, pág. 94].

Creo que el hecho de que lmk no se encuentre en el semítico occidental es más importante de lo que parece a simple vista.