Book of Moses Essay #39

Moses 1:25

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Matthew L. Bowen, David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock

Temple Names as Signposts on the Covenant Pathway

The use of temple names as signposts on the covenant pathway is ancient. It is reflected in the second-century account of the early Christian theologian, Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150-215 CE). His account is drawn from a group of “initiates” (= Greek mystai) who described the three successive names that they understood to have been given to Moses at different junctures of his life: “‘Joachim,’ given him by his mother at circumcision; ‘Moses,’ given him by Pharaoh’s daughter; and ‘Melchi,’1 a name he had in heaven which was given him, apparently by God, after his ascension.”2 Though interpretations of the name “Melchi” vary, the eminent scholar of Second Temple Judaism, Erwin Goodenough, saw it as representing the “eternal priesthood of Melchizedek,”3 reported in Genesis as being a “king” and “the priest of the Most High God.”4 Going beyond these three names reported in Clement’s account, Moses 1:25 can be seen as the bestowal of a final, fourth name, implied in the divine declaration that Moses is to be “made stronger than many waters.”

Who were the “initiates” from whom Clement received this information? It is possible that he received it as part of his own initiation into the mysteries of Christ, an event to which he alludes indirectly in his own writings.5 Among other things, such mysteries seem to have included unwritten temple teachings not to be shared with new Christian converts or with the world at large.6 In addition, a controversial letter purportedly written by Clement and discovered by Morton Smith, mentions certain “secret” doings and writings that were part of the “hierophantic teaching of the Lord [that would] lead the hearers into the innermost sanctuary of that truth,” but that were “most carefully guarded, being read only to those who are being initiated into the great mysteries.”7 Other alternatives have also been advanced. For example, although Clement “names as his immediate informants a circle of religious savants,” some scholars conclude that “the ultimate source” for this reference “was presumably a written document.”8

In support of the idea that the practice of applying a series of sacred names to individuals was known not only by some early Christians but also hundreds of years earlier in some strands of Second Temple Judaism, we turn to a non-sectarian Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript entitled the Visions of Amram. Texts such as this one might have attracted the attention of groups of Jewish initiates that outsiders called Essenes and Therapeutai about whom the Philo of Alexandria (ca. 15 BCE–45 CE) wrote in treatises with which Clement was very familiar.9 In one of three examples this naming pattern included in the Visions of Amram, an angel identifies his three names as being Michael, Prince of Light, and Melchizedek — the latter being interpreted as a title that means “Ruler of Righteousness.”10 In further support of the idea that the Michael’s third name of Melchizedek is meant as a title rather than as a unique individual name is that it corresponds to the third name of Moses as reported by Clement. Intriguingly, a later passage in the Visions of Amram seems to portend the giving to Moses of his own names.11 The relevant line begins with the words “I will tell you your(?) names,” but unfortunately the text breaks off there and the names are not mentioned elsewhere in the fragments.12

In this Essay, we will argue that the elegantly reflective, multi-lingual nuances of the series of names and titles ascribed to Moses by Clement’s initiates can be seen as various enriched likenesses of himself, interpreted and amplified to reveal the latent character and identity of the prophet as a “God in embryo.”13 Although we cannot know whether the report that a particular series of names was given to Moses is historically authentic, the suggestions remain of interest because the meanings of the names are so remarkably apropos. A series of names of this sort would have helped Moses to discover aspects of his past, present, and future destiny while also enabling him to accomplish his heavenly ascent. It does not seem impossible that the initiates who reported these names may have known that such names were meant to be used as “keywords” in heavenly or ritual ascent.

Below, we will argue that each one of the three “ciphered” names for Moses reported by Clement is rich in meaning when “deciphered” in light of Moses’ premortal and mortal mission. And, remarkably, when the fourth title (“stronger than many waters,” foreshadowing Moses’ eternal destiny) is appended to the rest, each member of the complete set of four names is arguably “present” in Moses 1.

We will begin with a brief overview of the function of names as “keywords” in temple contexts. We will then show how the four names he was purportedly given serve to illuminate Moses’ life and mission. Finally, we offer concluding thoughts about patterns of ritual and heavenly ascent.

Temple Names as “Keywords”

The idea of “keywords” has been associated with temples since very early times. In a temple context, the meaning of the term “keyword” can be taken quite literally: the use of the appropriate keyword or keywords by a qualified worshipper “unlocks” each one of a successive series of gates, thus providing access to specific, secured areas of the sacred space.14

In temples throughout the ancient Near East, including Jerusalem, “different temple gates had names indicating the blessing received when entering: ‘the gate of grace,’ ‘the gate of salvation,’ ‘the gate of life,’ and so on,”15 as well as signifying “the fitness, through due preparation, which entrants should have in order to pass through [each one of] the gates.”16 In Jerusalem, the final “gate of the Lord, into which the righteous shall enter,”17 very likely referred to “the innermost temple gate”18 where those seeking the face of the God of Jacob19 would find the fulfillment of their temple pilgrimage. The last gate, like each of those previously encountered, could be opened only to entrants who had passed every prior test. Importantly, these tests were designed not only to demonstrate knowledge relating to specific keywords but also to assess whether the entrant met the qualifications of moral fitness and experience.

These keywords can also be associated with names. As Joseph Smith taught, “The new name is the key word.”20 In this regard, it is important to understand that in each stage of that passage one was expected not only to know something but also to be something.21 Some ancient exegetes went so far as to assert: “all ancient traditions agree that the true name of a living thing reflects precisely its nature or its very essence.”22 For example, as René Guénon illustrates this particular view:23 “It is because Adam had received from God an understanding of the nature of all living things that he was able to give them their names” in the Garden of Eden.24 The idea of a strong connection between names and personal attributes is evident in Old Testament examples of figures such as Abraham, Sarah, and Jacob, who received new names only after they had been sufficiently tested and found worthy of them.25

Joachim

The first name, Joachim, meaning “Yahweh has raised up”26 is closely associated with the well-known prophecy of Moses in Deuteronomy 18:15 that speaks of a prophet “like unto” himself that the Lord will later “raise up.”

However, more pertinent to the present discussion than references to later prophets that the Lord would “raise up” is the question of how the meaning of the name “Joachim” — “Yahweh has raised up” — might be shown as being relevant to Moses himself, he being the one to whom these subsequent figures were likened. While no relevant passages justifying the application of the name to Moses are given in the Bible, these allusions to the meaning of the name appear in Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith Translation passages containing the prophecies of Joseph, son of Israel, long prior to Moses’ birth. In one of these passages, the Lord declared that He would surely “raise up” Moses “to deliver [Israel] out of the land of Egypt.”27

Thus, it is apparent that Joachim, the first name said to have been given to Moses — and which would have been consistent with the premortal foreordination he received in anticipation of his earthly mission — would have been completely at home if it had been explicitly included in Moses 1:41. There, the Lord, in subtle wordplay that functions by omission, refers directly to the meaning of the most important element of Moses’ first purported sacred name (“raise up”) without explicitly mentioning the name itself in the English text.

Moses

The Hebrew etymology of Moses is given in Exodus 2:10: “And she called his name Moses [mōšeh] and she said, Because I drew him out of the water.” On the other hand, the commonly accepted Egyptian origin of the name Moses means “begotten” or “born.” Significantly, the Egyptian form of the name Moses is typically paired with the name of a god, e.g., Ramesses (“Rēʿ is begotten”), Thutmose ( “Thoth is begotten”), Ahmose ( “the moon [-god] is begotten”), and so forth.

Despite the surface level differences between the Hebrew and Egyptian etymologies, it can be shown that the two derivations function very well together. To be “drawn” from evokes “birth” imagery of being “drawn” from amniotic waters.28 One can virtually substitute the meaning of the Egyptian verb for the meaning of the Hebrew verb in the explanation for Moses’ name in translation: “And she called his name Moses: and she said, ‘Because I birthed him from the water.’”29

Significantly, the words of Joseph in JST Genesis 50:29 further illuminate the dual derivation of ‘Moses’: “For a seer will I raise up to deliver my people out of the land of Egypt; and he shall be called Moses. And by this name he shall know that he is of thy house; for he shall be nursed by the king’s daughter, and shall be called her son.”30

Finally, it should be observed that Moses’ second name, the name he was given by his adoptive mother in Egypt and by which he was known throughout his mortal life, appears a remarkable twenty-five times within the forty-two verses of Moses 1. As we will see later on, the initial Hebrew and Egyptian meanings of the name “Moses” that can be seen in Exodus 2:10 anticipate the richer significance of the name that will unfold in Moses 1:25.

Melchi

Erwin Goodenough comments as follows with respect to “Melchi,” the third name of Moses that is reported by Clement: “The significance of ‘Melchi’ is not explained, but it at least suggests the eternal priesthood of Melchizedek.”31 In this context, we concur not only with Goodenough but also with Margaret Barker, who goes on to say that Melchizedek (Melchi-zedek32 ) should be regarded as a title as much as a name.33 According to Barker, the title:34

was associated with the original temple priesthood in Jerusalem, and it was a title that the first Christians gave to Jesus. … The account of Solomon’s enthronement in 1 Chronicles 29 originally described how he became the human presence of the Lord, the king (“I have begotten you with dew” [i.e., with a confirmatory anointing35 ], Psalm 110:3) and also the high priest (“a priest for eternity,” Psalm 110:4). He became Melchi (king) – Zedek (righteous one).

In this connection, it should be remembered that the blessings of the fulness of the Holy Priesthood, given to Moses and representing the roles of a king and priest, were originally connected not with the name of Melchizedek but rather with the “Son of God.”36 Only later was the name of “Melchizedek Priesthood” substituted as a description of this priesthood order, “out of respect or reverence” to the sacred name of the “Son of God,” so as “to avoid [its] too frequent repetition.”37

Thus there is no inconsistency in the fact that Moses 6:68 describes an individual who has received the fulness of the priesthood as having become, when divinely ratified, “a son of God.”38 This description resonates with the royal rebirth formula of Psalm 2:7: “Thou art my Son; this day have I begotten thee,” spoken on the occasion of the Davidic king’s enthronement.

Thus, we should not be surprised that God’s description of Moses as “my son” appears three additional times in Moses 139 — which we take, for the reasons just mentioned, as being equivalent to his being called “Melchizedek.” The importance of Moses’ status as “a son of God” is highlighted by Satan himself when the legitimacy of that title is the subject of the opening controversy in his challenge to the prophet.40

We further note that the declaration that Moses is “a son of God” hints at one possible reason why previously, in Exodus 2:10, he was given only “half a name.” Remember that the name “Moses” is lacking the theophoric prefix that is often present in the names of royal Egyptian figures with similar names, names like Ra-messes, Thut-mose, Ah-mose, and so forth. Remember that the names of these figures declared them to have been begotten as one or another of the Egyptian gods. Only now, in the account of Moses 1, is it revealed that Moses has been begotten with the name of the God of Israel, the heretofore missing theophoric prefix.

the Tetragrammaton in top center (detail), ca. 1616

“As If Thou Wert God”

The closest statement to the phrase “as if thou wert God” (Moses 1:25) in the Bible is found in Exodus 7:1. Surprisingly, the verse does not say that Moses was to be “like a god” to Pharaoh. Rather, the Lord’s words to the prophet in Hebrew read literally: “I have made you God/god to Pharaoh.”41 This concept has been difficult for some scholars to accept. For example, Gary Rendsburg sees “Moses’ [temporary] elevation to the divine plane” as violating “a basic tenet of the ancient Israelites” in order to respond to “the exigency of the moment.”42 However, there are both ancient and modern sources that argue that Moses’ divine status was neither exceptional nor provisional.

Moses as god and king. Drawing on Jewish sources, Wayne Meeks has written a classic chapter citing sources that portray Moses as “God and King.”43

In some accounts, Moses’ divine status is associated with that of Yahweh. For example, the promise to Moses of power over the waters resembles that given to David in Psalm 89:25.44 Like Moses, David is there depicted as a god — a “lesser YHWH” — on earth,45 consistent with the extended discussion by David J. Larsen of the enthronement of Moses and other figures in the literature of the ancient Near East.46

In other accounts, Moses’ ultimate divine status is compared to Elohim rather than Yahweh. For example, Wayne Meeks finds instances in the Samaritan literature where “the name with which Moses was ‘crowned’ or ‘clothed’ is … Elohim.”47 He further reports that the name of Elohim, conferred on Moses, was “distinguished from YHWH, ‘the name which god revealed to him’”48 on Mount Sinai.49

The theme of God’s personal disclosure of His own name to those who approach the final gate to enter His presence is reminiscent of the explanation of Figure 7, Facsimile 2 from the Book of Abraham. In the Prophet’s interpretation of that figure, God is described as “sitting upon his throne, revealing through the heavens the grand Key-words of the Priesthood.” The same concept was operative elsewhere in the ancient Near East. For example, in the Old Babylonian investiture liturgy, we might see in the account of the fifty names given to Marduk at the end of Enuma Elish a description of his procession through the ritual complex in which he took upon himself the divine attributes represented by those names one by one.50 Ultimately, it seems, he would have passed the guardians of the sanctuary gate to reach the throne of Ea where, as also related in the account, he finally received the god’s own name and a consequent fusion of identity with the declaration: “He is indeed even as I.”51

The “rod” and “word” of Moses as symbols of his authority. Of interest in this context is that the “rod” and the “word” of Moses are associated with the authority of God through Egyptian and Hebrew wordplay. This wordplay is woven throughout both ancient and modern accounts of the life of Moses (e.g., the slaying of the Egyptian, the crossing of the sea, and the smiting of the rock).

In connection with this idea, Nephi’s multi-lingual puns on “rod” and “word” revolve around the polysemy of Egyptian term for “rod, staff”; “word” and the homonymy of the Egyptian term with the Hebrew maṭṭeh (“rod,” “staff”), the latter Hebrew term perhaps being derived from the Egyptian former.52 Moses’ repeated use of “word” and “rod” in close proximity brings together the “word of God” as creative act (“word of my power”) with power of command over the “many waters”53 and the “word of God” as scripture: “and he shall smite the waters of the Red Sea with his rod. And he shall have judgment, and shall write the word of the Lord”;54 “I will raise up a Moses; and I will give power unto him in a rod; and I will give judgment unto him in writing.”55

Moses the deliverer. Remarkably, the Hebrew derivation of Moses’ name is invoked in another elegant literary twist. Moses, who was said in Exodus 2:10 to have been delivered from the water as a weak and helpless infant, is told in Moses 1:25 that he is to be “made stronger than many waters.”56 The most obvious allusion here is to the power Moses will be given to divide the Red Sea.57 However, the phrase also recalls God’s subduing of the waters at Creation, particularly in light of the phrase that follows: “as if thou wert God.” Moreover, as God Himself explains the significance of Moses’ name, He links it with one of His own titles: “Almighty.”58 Fittingly, the divine name of “Almighty”59 in Moses 1:4, 25 is also closely tied to the demonstration of God’s power over the waters of chaos as the first act of Creation60 as well as the divine destruction of the Egyptian army.61

Consistent with this idea, ancient sources universally witness that the name Moses, rather than suggesting the “passive” meaning of one who is “drawn” or “pulled” out of the water as one would expect in the context of the naming scene in Exodus, is instead vowelled as a “pseudo-active” participle suggesting his future as one who will “draw” or “pull” others out of the water.62 The “many waters” or “great waters” ultimately obeyed Moses’ “command even as if [he] wer[e] God” (Moses 1:25–26) as he provided temporal deliverance to the Israelites at the time of the Exodus. Moses also used the same divine authority—the authority with which one “draws” or “pulls” (mōšeh) from the water—to deliver the Israelites spiritually through baptism.63 Elder Bruce R. McConkie commented on this idea as follows:64

Moses—mighty, mighty Moses—acting in the power and authority of the holy order, gathered Israel once. What is more fitting than for him to confer upon mortals in this final dispensation the power and authority to lead latter-day Israel out of Egyptian darkness, through a baptismal Red Sea, into their promised Zion?.65

In summary, speaking of Christ as the premortal prototype not only for Moses, but also for all those who were foreordained to priestly offices and subsequently ordained in mortal life, the Gospel of Philip suggests that the general meaning, symbolism, and sequence of the ordinances has always been the same: “He who … [was begotten] before everything was begotten anew. He [who was] once [anointed] was anointed anew. He who was redeemed in turn redeemed (others).”66 Thus, in the declaration that Moses is to be “made stronger than many waters,”67 God is saying that Moses, the delivered, will now become Moses, the deliverer.68

Conclusion

We have seen how the four names that were said to have been given to Moses fittingly summarize the whole of his divinely appointed mission. “Joachim,” a personal name that is first in sequence, anticipated the mission he was “raised up” to fulfill in the premortal world. The second, “Moses,” also a personal name, reflected the dual role he played during his mortal life as an Egyptian prince and a Hebrew prophet. The title “Melchi” was bestowed upon Moses “after his ascension” when he became “a son of God,” holding the fulness of the higher priesthood and, in likeness of Melchizedek, becoming a king and a priest forever in the holy order. And his final, fourth name was a title that represented the name of God the Father Himself. Philo Judaeus likewise argued that Moses was not only as a prophet, priest, and king, but also (like Jesus) a god, having been “changed into the divine” through his initiation into the “mysteries.”69

Elsewhere it has been argued that the narrative of Moses’ visions in chapter 1 of the Book of Moses fits squarely into the ancient literary genre of “heavenly ascent.”70 But there is evidence that the symbolism of this journey may also have been enacted in various forms of ritual ascent among Jews and early Christians. For example, in his discussion of late Second Temple Jewish mysticism, Erwin Goodenough summarized Philo’s descriptions of “two successive initiations within a single Mystery,” constituting “a ‘Lesser’ Mystery in contrast with a ‘Greater,’” as follows:

For general convenience we may distinguish them as the Mystery of Aaron and the Mystery of Moses. The Mystery of Aaron got its symbolism from the great Jerusalem cultus. … The Mystery of Moses … led the worshipper above all material association; he died to the flesh, and in becoming reclothed in a spiritual body moved progressively upwards … and at last ideally to God himself. … The objective symbolism of the Higher Mystery was the holy of holies with the ark, a level of spiritual experience which was no normal part of even the high-priesthood. Only once a year could the high priest enter there, and then only … when so blinded by incense that he could see nothing of the sacred objects within. The Mystery of Aaron was restricted to the symbolism of the Aaronic high priest.71

According to Goodenough “Philo had himself been ‘initiated under Moses’ [i.e., received the mysteries of the higher priesthood] and it seems to me quite likely that the Elder Samuel [who built the synagogue of Dura Europos] may have been so ‘initiated’ also.72 Hinting at the possibility of such ritual in the synagogue at Dura Europos, Goodenough noted: “In [a] side room were benches and decorations that mark the room as probably one of cult, perhaps an inner room, where special rites were celebrated by a select company. … So far as structure goes, it might have been the room for people especially ‘initiated’ in some way.”73 Bradshaw has written at length how the Ezekiel mural at the synagogue might be seen as a witness of ancient Jewish mysteries of the sort that Philo described.74 The controversial idea of initiation rites at the Dura synagogue receives support from Crispin Fletcher-Louis’ subsequent findings on what he calls the “angelomorphic priesthood” of the Qumran community.75 Of equal significance is David Calabro’s research hinting that the Christian Church at Dura Europos, just down the road from the synagogue, may have likewise partaken of teachings and ordinances of an esoteric nature, including baptism for the dead.76

In all this Moses was not only the model disciple, but also the model leader. Observes Old Testament scholar C. T. R. Hayward: “Philo saw nothing improper … in describing Moses as a hierophant: like the holder of that office in the mystery cults of Philo’s day, Moses was responsible for inducting initiates into the mysteries, leading them from darkness to light, to a point where they are enabled to see [God].”77 Hayward’s view echoes the teachings of Doctrine and Covenants 84:21–23:

21 And without the ordinances thereof, and the authority of the priesthood, the power of godliness is not manifest unto men in the flesh;

22 For without this no man can see the face of God, even the Father, and live.

23 Now this Moses plainly taught to the children of Israel in the wilderness, and sought diligently to sanctify his people that they might behold the face of God.

This article is adapted from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. “‘Made Stronger Than Many Waters’: The Names of Moses as Keywords in the Heavenly Ascent of Moses.” In Proceedings of the Fifth Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 7 November 2020, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple on Mount Zion 6, in preparation. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2020. www.templethemes.net.

Further Reading

Bowen, Matthew L. “‘What meaneth the rod of iron?’.” FARMS Insights 25, no. 2 (2005): 2–3. https://archive.bookofmormoncentral.org/sites/default/files/archive-files/pdf/farms-staff/2019-10-07/insights_25-2.pdf. (accessed July 11, 2020).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?” BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4–49. www.templethemes.net.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 53–79. www.templethemes.net.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. “Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): in press.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. “‘Made Stronger Than Many Waters’: The Names of Moses as Keywords in the Heavenly Ascent of Moses.” In Proceedings of the Fifth Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 7 November 2020, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple on Mount Zion 6, in preparation. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2020. www.templethemes.net.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, p. 31.

Johnson, Mark J. “The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145–186. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Nibley, Hugh W. “To open the last dispensation: Moses chapter 1.” In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless: Classic Essays of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 1–20. Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1978, p. 12.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, pp. 220–221.

Reynolds, Noel B, and Jeff Lindsay. “‘Strong like unto Moses’: The case for ancient roots in the Book of Moses based on Book of Mormon usage of related content apparently from the Brass Plates.” Presented at the conference entitled “Tracing Ancient Threads of the Book of Moses’ (September 18–19, 2020), Provo, UT: Brigham Young University 2020.

References

Adler, William. “Introduction.” In The Jewsih Apocalyptic Heritage in Early Christianity, edited by James C. VanderKam and William Adler, 1-31. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996.

Arp, Nathan J. “Joseph knew first: Moses the Egyptian son.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 32 (2019): 187-98. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/joseph-knew-first-moses-the-egyptian-son/. (accessed July 11, 2020).

Baker, LeGrand L., and Stephen D. Ricks. Who Shall Ascend into the Hill of the Lord? The Psalms in Israel’s Temple Worship in the Old Testament and in the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2009.

Barker, Margaret. “Who was Melchizedek and who was his God?” Presented at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Session S19-72 on ‘Latter-day Saints and the Bible’, San Diego, CA, November 17-20, 2007.

———. King of the Jews: Temple Theology in John’s Gospel. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2014.

Bednar, David A. Power to Become: Spiritual Patterns for Pressing Forward with a Steadfastness in Christ. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2014.

Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible, Featuring the Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Biale, David. “The god with breasts: El SHaddai in the Bible.” History of Religions 21, no. 3 (February 1982): 240–56. https://www.academia.edu/35615351/David_Biale_The_God_with_Breasts_El_Shaddai_in_the_Bible_History_of_Religions_21_3_February_1982_240_256. (accessed November 23, 2020).

Bowen, Matthew L. “‘What meaneth the rod of iron?’.” FARMS Insights 25, no. 2 (2005): 2-3. https://archive.bookofmormoncentral.org/sites/default/files/archive-files/pdf/farms-staff/2019-10-07/insights_25-2.pdf. (accessed July 11, 2020).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. “The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?” BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4-49. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol49/iss1/2/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. “The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East.” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol4/iss1/1/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/details/151128TempleThemesInTheOathAndCovenantOfThePriesthood2014Update ; https://archive.org/details/140910TemasDelTemploEnElJuramentoYElConvenioDelSacerdocio2014UpdateSReading. (accessed November 29, 2020).

———. 2018. What Did the Lord Mean When He Said Moses Would Become “God to Pharaoh” During the Plagues of Egypt? (Old Testament KnoWhy JBOTL013A, 26 March 2018). In Interpreter Foundation. https://interpreterfoundation.org/knowhy-otl13a-what-did-the-lord-mean-when-he-said-moses-would-become-god-to-pharaoh-during-the-plagues-of-egypt-2/. (accessed July 4, 2020).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. “Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 38 (2020): 179-290. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/moses-1-and-the-apocalypse-of-abraham-twin-sons-of-different-mothers/. (accessed July 29, 2020).

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Calabro, David. “From temple to church: Defining sacred space in the Near East.” In Proceedings of the Fifth Interpreter Foundation Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 7 November 2020, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple on Mount Zion 6, in preparation. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2020.

Clement of Alexandria. ca. 190-215. “The Stromata, or Miscellanies.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers (The Writings of the Fathers Down to AD 325), edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. 10 vols. Vol. 2, 299-568. Buffalo, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1885. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

Cumming, Sam. 2019. Names (Revision of 26 June 2019). In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/names/. (accessed November 3, 2020).

Dalgaard, Kasper. 2013. A Priest for All Generations: An Investigation into the Use of the Melchizedek Figure from Genesis to the Cave of Treasures (Volume 48, Det Teologiske Fakultet). In University of Copenhagen Department of Theology. https://static-curis.ku.dk/portal/files/188645800/48_Kasper_Dalgaard_A_Priest_for_All_Generations_e_bog.pdf. (accessed August 10, 2020).

DelCogliano, Mark. Basil of Caesarea’s Anti-Eunomian Theory of Names: Christian Theology and Late-Antique Philosophy in the Fourth Century Trinitarian Controversy. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 103. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2010. https://brill.com/view/title/17416 ; https://www.google.com/books/edition/Basil_of_Caesarea_s_Anti_Eunomian_Theory/Td95DwAAQBAJ . PDF of Emory University Doctoral Dissertation: https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/qr46r085k?locale=en.

Dolkart, Judith F., ed. James Tissot, The Life of Christ: The Complete Set of 350 Watercolors. New York City, NY: Merrell Publishers and the Brooklyn Museum, 2009.

Duke, Robert R. The Social Location of the ‘Visions of Amram’ (4Q543-547). New York City, NY: Peter Lang, 2010. https://books.google.com/books?id=knLh2SnxQ0AC. (accessed July 3, 2020).

Eaton, John H. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation. London, England: T&T Clark, 2003.

Eccles, Robert S. Erwin Ramsdell Goodenough: A Personal Pilgrimage. Society of Biblical Literature, Biblical Scholarship in North America, ed. Kent Harold Richards. Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1985.

Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Etheridge, J. W., ed. The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch, with the Fragments of the Jerusalem Targum from the Chaldee. 2 vols. London, England: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1862, 1865. Reprint, Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2005. http://www.targum.info/pj/psjon.htm. (accessed August 10, 2007).

Faulconer, James E. “Self-image, self-love, and salvation.” Latter-day Digest 2, June 1993, 7-26. http://jamesfaulconer.byu.edu/selfimag.htm. (accessed August 10, 2007).

Ferguson, John. “The achievement of Clement of Alexandria.” Religious Studies 12, no. 1 (1976): 59–80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20005313. (accessed December 7, 2020).

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. “‘Now this Melchizedek…’ (Heb 7,1).” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1963): 305-21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43712272. (accessed November 3, 2020).

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. All the Glory of Adam: Liturgical Anthropology in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Fossum, Jarl E. The Name of God and the Angel of the Lord: Samaritan and Jewish Concepts of Intermediation and the Origin of Gnosticism. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 36. Tübingen, Germany: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1985.

Foster, Benjamin R. “Epic of Creation.” In Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, edited by Benjamin R. Foster. Third ed, 436-86. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2005.

Gee, John. “The keeper of the gate.” In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks. Temples Throughout the Ages 2, 233-73. Provo, UT: FARMS at Brigham Young University, 1999.

Goodenough, Erwin Ramsdell. By Light, Light: The Mystic Gospel of Hellenistic Judaism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1935.

———. Symbolism in the Dura Synagogue. 3 vols. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period 9-11, Bollingen Series 37. New York City, NY: Pantheon Books, 1964.

———. Summary and Conclusions. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period 12, Bollingen Series 37. New York City, NY: Pantheon Books, 1965.

Gross, Andrew D. “Visions of Amram [4Q543-549].” In Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, edited by Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel and Lawrence H. Schiffman. 3 vols. Vol. 2, 1507-10. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2013.

Guénon, René. Symboles fondamentaux de la Science sacrée. Paris, France: Gallimard, 1962.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Hayward, C. T. R. Interpretations of the Name Israel in Ancient Judaism and Some Early Christian Writings: From Victorious Athlete to Heavenly Champion. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Isenberg, Wesley W. “The Gospel of Philip (II, 3).” In The Nag Hammadi Library, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 139-60. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Jacobson, Howard, ed. A Commentary on Pseudo-Philo’s Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum, with Latin Text and English Translation. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996.

———. “Pseudo-Philo, Book of Biblical Antiquities.” In Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, edited by Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel and Lawrence H. Schiffman. 3 vols. Vol. 1, 470-613. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2013.

Johnson, Mark J. “The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Jones, Robert. “Priesthood and cult in the Visions of Amram: A critical evaluation of its attitudes toward the contemporary temple establishment in Jerusalem.” Dead Sea Discoveries 27, no. 1 (2020): 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685179-12341504. (accessed August 10, 2020).

Jurgens, Blake Alan. “Reassessing the dream-vision of the Vision of Amram (4Q543–547).” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 24, no. 1 (2014): 3–42.

Knohl, Israel. “Sacred architecture: The numerical dimenions of biblical poems.” Vetus Testamentum 62 (2012): 189–97. https://www.academia.edu/1565388/Sacred_Architecture_The_Numerical_Dimensions_of_Biblical_Poems. (accessed December 12, 2020).

Kobelski, Paul J. Melchizedek and Melchireša’. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 10. Washington, DC: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1981.

Kugel, James L. The God of Old: Inside the Lost World of the Bible. New York City, NY: The Free Press, 2003.

Larsen, David J. “Psalm 24 and the two YHWHs at the gate of the temple.” In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 201-23. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

———. “And He Departed From the Throne: The Enthronement of Moses in Place of the Noble Man in Exagoge of Ezekiel the Tragedian (Originally prepared as a term paper for a Master’s Degree, Theology 228, Dr. Andrei A. Orlov, Marquette University, Fall 2008).” Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Session on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism, 23 November 2009, New Orleans, Louisiana. https://www.academia.edu/385529/_And_He_Departed_from_the_Throne_The_Enthronement_of_Moses_in_Place_of_the_Noble_Man_in_Exagoge_of_Ezekiel_the_Tragedian. (accessed August 3, 2019).

Lindsay, Jeffrey Dean. ““Arise from the Dust”: Insights from Dust-Related Themes in the Book of Mormon. Part 1: Tracks from the Book of Moses.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 179-232. https://s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/jnlpdf/lindsay-v22-2016-pp179-232-PDF.pdf. (accessed August 7, 2019).

———. Personal Communication to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, August 5, 2019.

Litwa, M. David. “The deification of Moses in Philo of Alexandria.” The Studia Philonica Annual 26 (2014): 1–27. https://www.academia.edu/16406623/The_Deification_of_Moses_in_Philo_of_Alexandria. (accessed November 3, 2020).

Lowy, Simeon. The Principles of Samaritan Bible Exegesis. Studia Post-Biblica 28, ed. J. C. H. Lebram. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1977.

Marmorstein, A. 1920-1937. The Doctrine of Merits in Old Rabbinical Literature and The Old Rabbinic Doctrine of God (1. The Names and Attributes of God, 2. Essays in Anthropomorphism) (Three Volumes in One). New York City, NY: KTAV Publishing House, 1968.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. “11QMelchizedek (11Q13 [11QMelch]).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 139-40. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

McConkie, Bruce R. “The ten blessings of the priesthood.” Ensign 7, November 1977, 33-35.

———. The Mortal Messiah: From Bethlehem to Calvary. 4 vols. The Messiah Series 2-5, ed. Bruce R. McConkie. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1979-1981.

———. A New Witness for the Articles of Faith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1985.

Meeks, Wayne A. “Moses as God and King.” In Religions in Antiquity: Essays in Memory of Erwin Ramsdell Goodenough, edited by Jacob Neusner. Religions in Antiquity, Studies in the History of Religions (Supplements to Numen) 14, 354-71. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1968.

Milik, Józef Tadeusz. “4Q Visions de ‘Amram et une citations d’Origène.” Revue Biblique 79, no. 1 (1972): 77-97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44088133. (accessed August 10, 2020).

Mowinckel, Sigmund. 1962. The Psalms in Israel’s Worship. 2 vols. The Biblical Resource Series, ed. Astrid B. Beck and David Noel Freedman. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004.

Nelson, Russell M. “Let God prevail.” Ensign 50, November 2020. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2020/10/46nelson?lang=eng. (accessed October 14, 2020).

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Oaks, Dallin H. “The challenge to become.” Ensign 30, November 2000, 32-34.

Parry, Donald W. “Temple worship and a possible reference to a prayer circle in Psalm 24.” BYU Studies 32, no. 4 (1992): 57-62.

Parry, Donald W., and Emanuel Tov, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader Second ed. Vol. 1. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013.

Philo. “On the Life of Moses.” In Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, edited by Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel and Lawrence H. Schiffman. 3 vols. Vol. 1. Translated by Maren R. Niehoff, 959-88. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2013.

———. b. 20 BCE. “On the Cherubim (De Cherubim).” In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. 12 vols. Vol. 2. Translated by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. The Loeb Classical Library 227, ed. Jeffrey Henderson, 3-85. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1929.

———. b. 20 BCE. “On the Giants (De Gigantibus).” In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. 12 vols. Vol. 2. Translated by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. The Loeb Classical Library 227, ed. Jeffrey Henderson, 441-79. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1929.

———. b. 20 BCE. “Moses 1 and 2 (De Vita Mosis).” In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson. Revised ed. 12 vols. Vol. 6. Translated by F. H. Colson. The Loeb Classical Library 289, 274-595. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935.

———. b. 20 BCE. Philo Supplement 2 (Questions on Exodus). Translated by Ralph Marcus. The Loeb Classical Library 401, ed. Jeffrey Henderson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953.

Rendsburg, Gary A. “Moses as equal to Pharaoh.” In Text, Artifact, and Image: Reveling Ancient Israelite Religion, edited by Gary A Beckman and Theodore J. Lewis. Brown Judaic Studies 346, 201-19. Providence, RI: Brown Judaic Studies, 2006. http://jewishstudies.rutgers.edu/faculty/core-faculty-information/gary-a-rendsburg/132-publications-of-gary-a-rendsburg. (accessed March 19, 2018).

Reynolds, Noel B., and Jeff Lindsay. “‘Strong like unto Moses’: The case for ancient roots in the Book of Moses based on Book of Mormon usage of related content apparently from the Brass Plates.” Presented at the conference entitled “Tracing Ancient Threads of the Book of Moses’ (September 18-19, 2020), Provo, UT: Brigham Young University 2020.

Runia, David T. “Clement of Alexandria and the Philonic doctrine of the divine powers.” Vigilae Christianae 58, no. 3 (August 2004): 256–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1584621. (accessed December 7, 2020).

Schäfer, Peter. The Jewish Jesus: How Judaism and Christianity Shaped Each Other. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Secret Gospel of Mark. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secret_Gospel_of_Mark. (accessed December 7, 2020).

Shelemon. ca. 1222. The Book of the Bee, the Syriac Text Edited from the Manuscripts in London, Oxford, and Munich with an English Translation. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. Reprint ed. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1886. Reprint, n. p., n. d.

Smith, Morton. 1982. The Secret Gospel: The Discovery and Interpretation of the Secret Gospel According to Mark. Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press, 2005.

Speiser, Ephraim A. “The Creation Epic (Enuma Elish).” In Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, edited by James B. Pritchard. 3rd with Supplement ed, 60-72, 501-03. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1972.

Sprengling, Martin, and William Creighton Graham, eds. Barhebraeus’ Scholia on the Old Testament, Part 1: Genesis-2 Samuel. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 13. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1931. https://archive.org/details/SprenglingGraham1931BarhebraeusScholia. (accessed July 3, 2020).

Talmage, James E. The Story of ‘Mormonism’ and The Philosophy of ‘Mormonism’. Salt Lake City, UT: The Deseret News, 1914. https://archive.org/details/storyofmormonism00talmi. (accessed July 5, 2020).

———. 1899. The Articles of Faith. 1924 Revised ed. Classics in Mormon Literature. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1984.

Talon, Philippe. “Enūma Eliš and the transmission of Babylonian cosmology to the West.” In Mythology and Mythologies: Methodological Approaches to Intercultural Influences. Proceedings of the Second Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project. Held in Paris, France, October 4-7, 1999, edited by R. M. Whiting, 265-77. Helsinki, Finland: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 2001. http://www.aakkl.helsinki.fi/melammu/. (accessed March 10, 2011).

Tissot, J. James. The Old Testament: Three Hundred and Ninety-Six Compositions Illustrating the Old Testament, Parts 1 and 2. 2 vols. Paris, France: M. de Brunhoff, 1904.

Tromp, Johannes. The Assumption of Moses: A Critical Edition with Commentary. Studia In Veteris Testamenti Pseudepigrapha 10, ed. A.-M. Denis and M. De Jonge. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1993. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/11203. (accessed July 3, 2020).

Vermes, Geza. “Essenes – Therapeutai – Qumran.” Durham University Journal (June 1960): 97–115.

———. “The etymology of ‘Essenes’.” Revue de Qumrán 2, no. 3 (1960): 427–43. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24599235. (accessed December 7, 2020).

———. “Essenes and Therapeutai.” Revue de Qumrán 3, no. 4 (1962): 495–504. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24599295. (accessed December 7, 2020).

Wells, Bruce. “Exodus.” In Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, edited by John H. Walton. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

Young, Brigham. 1874. “The calling of the priesthood, to preach the Gospel and proceed witht eh organization of the kingdom of God, preparatory to the coming of the Son of Man; all good is of the Lord; salvation and life everlasting are before us (Discourse by President Brigham Young, delivered in the Bowery, at Brigham City, Saturday Morning, June 26, 1874).” In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 17, 113-15. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1884. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Zinner, Samuel. Personal communication to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, November 3, 2020.

———. Recovering ancient Hebrew scribal numerical and acrostic techniques, in preparation.

Notes on Figures

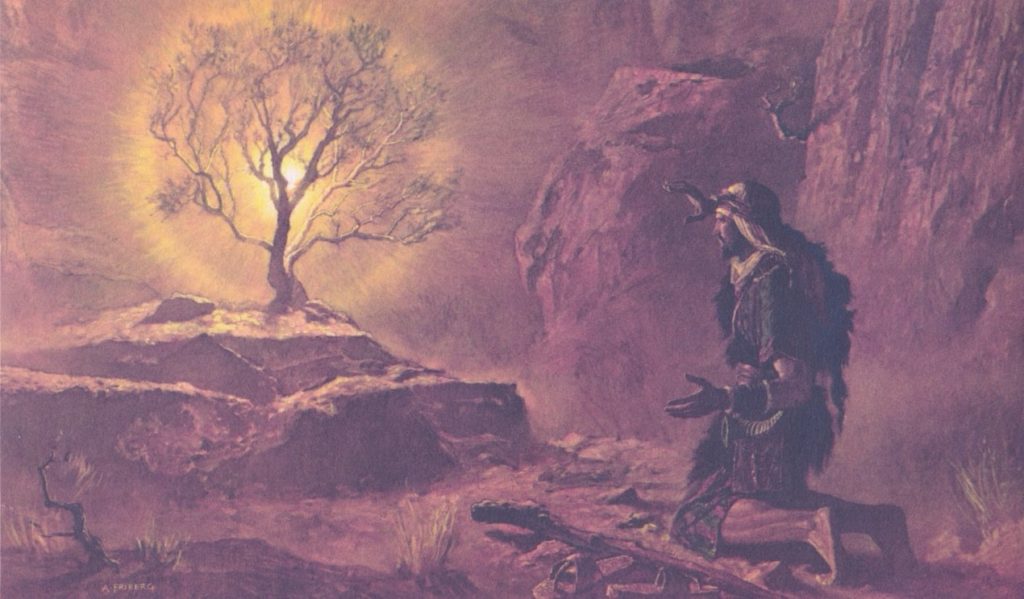

Figure 1. BYU Magazine, Fall 2017, https://magazine.byu.edu/article/eight-heads-ten-commandments/ (accessed July 12, 2020). “Through the generosity of Rex G. (’62) and Ruth Methvin Maughan (BS ’60), BYU acquired eight Arnold Friberg portraits used for Cecil B. Demille’s The Ten Commandments. Photo by Roger Layton.” With permission from Bruce Patrick, Art Director, BYU Magazine.

Figure 2. Image: 8 7/8 x 16 3/8 in. (22.5 x 41.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.7. Published in J. F. Dolkart, James Tissot, p. 204. With permission.

Figure 3. With the kind permission of Glen Hopkinson, son of Harold I. Hopkinson. As published in “The Foreordination of Abraham,” Book of Abraham Insight #21, https://www.pearlofgreatpricecentral.org/the-foreordination-of-abraham/ (accessed October 14, 2020).

Figure 4. From 1957 packet containing reprints of a series of inserts which appeared in “The Instructor” magazine beginning in March 1957 (https://ia802800.us.archive.org/2/items/instructor923dese/instructor923dese.pdf [accessed July 12, 2020]). © 1957 by The Arnold Friberg Foundation and Friberg Fine Arts.

Figure 5. Offerings. J. J. Tissot, Old Testament, 1:47. The Jewish Museum, No. 52–94. Public domain. See Genesis 14:18–20.

Figure 6. The British Museum, Asset Number 978337001, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/978337001. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license for non-commercial use.

Figure 7. From 1957 packet containing reprints of a series of inserts which appeared in “The Instructor” magazine beginning in March 1957 (https://ia802800.us.archive.org/2/items/instructor923dese/instructor923dese.pdf [accessed July 12, 2020]). © 1957 by The Arnold Friberg Foundation and Friberg Fine Arts.

Figure 8. From 1957 packet containing reprints of a series of inserts which appeared in “The Instructor” magazine beginning in March 1957 (https://ia802800.us.archive.org/2/items/instructor923dese/instructor923dese.pdf [accessed July 12, 2020]). © 1957 by The Arnold Friberg Foundation and Friberg Fine Arts.

Figure 9. From 1957 packet containing reprints of a series of inserts which appeared in “The Instructor” magazine beginning in March 1957 (https://ia802800.us.archive.org/2/items/instructor923dese/instructor923dese.pdf [accessed July 12, 2020]). © 1957 by The Arnold Friberg Foundation and Friberg Fine Arts.

Footnotes

1 Other sources where this name or similar variants appear include (H. Jacobson, Pseudo-Philo, pp. 492-493 n. 9:16; R. R. Duke, Social Location, p. 75): Melchiel (“God is my king” H. Jacobson, Pseudo-Philo, 9:16, p. 492; 135 BCE-100 CE), Melchias (“king” George Syncellus, Chronographia (9th century CE) and George Cedrenus, Synopsis historion (11th-12th centuries CE), Amlâkâ (Shelemon, Book of the Bee, 29, p. 48), Malkēl (probably a corruption of “Malkel” — “God has ruled” M. Sprengling et al., Barhebraeus’ Scholia, Part 1, pp. 102-103; 13th century C), and Yamkil (Ishodad, Commentary on Exodus, 2:10, cited in H. Jacobson, Pseudo-Philo, p. 493 n. 9:16).

Robert Duke (R. R. Duke, Social Location, pp. 69-79) suggests that the Visions of Amram 1:9 records “Moses’ original Hebrew name. He renders the Aramaic ml’kyh, [more commonly] translated as “the messengers” as the Hebrew name, Malachiah, which he argues refers to Moses” (A. D. Gross, Visions of Amram, p. 1508 n. 1:9). Differing in this regard with Duke, Edward Cook, along with Gross, translate the passage as “the messengers” (D. W. Parry et al., DSSR (2013), 4Q583, Fragment 1 a-c, line 10, p. 883; A. D. Gross, Visions of Amram, 1:9, p. 1508).

2 E. R. Goodenough, Light, pp. 292-293. The whole of the relevant passage in the writings of Clement reads as follows (Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 1:23, p. 335 (ca. 198-203 CE)):

Thereupon the [Egyptian] queen gave the babe the name of Moses, with etymological propriety, from his being drawn out of the water, — for the Egyptians call water mou,— in which he had been exposed to die. For they call Moses one who breathed [on being taken] from the water. It is clear that previously the parents gave a name to the child on his circumcision; and he was called Joachim. And he had a third name in heaven, after his ascension, as the mystics say — Melchi.

Apart from the digression on the names given to Moses at circumcision and “in heaven,” Clement’s account is based on Philo, Moses, 1:5, op. 279ff.

3 E. R. Goodenough, Light, pp. 292-293. See Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 1:23, p. 335 (ca. 198-203 CE).

4 Genesis 14:18. See also JST Genesis 14:25–40.

5 Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 1:5, p. 307. For more about Clement’s view of Christianity as a “mystery religion,” see J. Ferguson, Achievement of Clement, pp. 62–63.

6 Mark 4:11. Cf. M. Barker, King of the Jews, p. 84.

7 Purported letter of Clement to Theodore, published in M. Smith, Secret Gospel, p. 14. Though some scholars dispute the nature of the “Secret Gospel of Mark” cited in the latter and some of Smith’s interpretations, most accept that the letter is an excellent match to the style of Clement. Hugh Nibley cites the work without qualification in H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), p. 515. For a summary of the debate on the nature and authenticity of this document, see, e.g., B. D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities, pp. 67–89; Secret Gospel, Secret Gospel.

8 W. Adler, Introduction, p. 22. Whereas J. Tromp, Assumption of Moses, pp. 270-285 argues that Clement obtained his information from the lost ending of the pseudepigraphal Assumption of Moses (ca. 100 BCE–100 CE), some other scholars hold differing views (see W. Adler, Introduction, p. 22 n. 96).

9 For more on these groups and their names, see G. Vermes, Etymology of ‘Essenes’; G. Vermes, Essenes – Therapeutai – Qumran; G. Vermes, Essenes and Therapeutai. On Clement’s familiarity with the writings of Philo, see D. T. Runia, Clement, pp. 256–258.

10 The extant text and English translation of the relevant passage is published in D. W. Parry et al., DSSR (2013), 4Q544 (4QVisions of ’Amramb ar), fragment 2 line 13 and fragment 3 line 2, p. 891. Though the complete set of names is not preserved in the extant text, J. T. Milik has made a strong case for his reconstruction of the missing names based on related texts (11Q13 and 1QM 13 1. 10–11. See J. T. Milik, 4Q Visions de ‘Amram, pp. 85-86; P. J. Kobelski, Melchizedek and Melchireša’, p. 28; K. Dalgaard, A Priest for All Generations, pp. 57-60). Here is text, with reconstructed portions shown within brackets:

[And these are his three names: Belial, Prince of Darkness], and Melchiresha’ … [and he answered and sa]id to me: [My] three names [are Michael, Prince of Light and Melchizedek].

“Milik and others since him have found this hypothetical list of names to represent the most plausible reconstruction of the surviving text” (ibid., p. 58). For a brief overview of Melchizedek in Second Temple literature, see B. A. Jurgens, Reassessing the Dream-Vision, pp. 29-33

11 According to R. Jones, Priesthood and Cult, p. 17 n. 69, at 4Q545, fragment 4 line 15b “the angelus interpres has likely just finished a description of Moses in the material preceding line 15, and is now beginning a description of Moses’ brother Aaron.” Thus, according to this view, the statement “I will tell you your(?) names” is being addressed to Moses.

12 D. W. Parry et al., DSSR (2013), 4Q545 (4QVisions of ’Amramc ar), fragment 4 line 14, p. 895.

13 J. E. Talmage, Articles (1984), p. 474 n. 4, citing J. E. Talmage, Story and Philosophy of ‘Mormonism’, p. 109.

14 See, e.g., S. Mowinckel, Psalms, 1:180, 1:181 n. 191; J. H. Eaton, Psalms Commentary, 118:19–22, p. 405; J. Gee, Keeper; J. M. Bradshaw et al., Investiture Panel, pp. 11, 20–22.

15 S. Mowinckel, Psalms, 1:181 n. 191.

16 J. H. Eaton, Psalms Commentary, 118:19–22, p. 405. See also Psalm 24:3–4.

17 Psalm 118:20.

18 S. Mowinckel, Psalms, 1:180.

19 Psalm 24:6. Donald Parry sees an allusion to a prayer circle in this verse (D. W. Parry, Psalm 24).

20 D&C 130:11, emphasis added.

21 See D. H. Oaks, To Become, p. 32. See also J. E. Faulconer, Self-Image; D. A. Bednar, Power to Become, pp. 1–35.

22 R. Guénon, Symboles, p. 36. Others, such as Basil of Caesarea in the 4th century, held, less radically, that each name had a distinct primary meaning, or notion, as well as signifying, secondarily, certain properties, but not essence itself (M. DelCogliano, Basil of Caesarea’s Anti-Eunomian Theory of Names, pp. 153–260). For a discussion of modern name theory, see S. Cumming, Names

23 R. Guénon, Symboles, p. 36, emphasis added.

24 Genesis 2:19–20.

25 Genesis 17:5, 15; 32:28.

26 F. Brown et al., Lexicon, p. 220c.

27 2 Nephi 3:10. Cf. v. 17; JST Genesis 50:26, 28.

28 Philo (like Josephus ) gave a derivation from Egyptian, explaining that “Mou is the Egyptian word for water” (Philo, On the Life of Moses, 1:17, p. 168). Niehoff explains: “Philo’s interpretation takes into account the historical background of the story, assuming that it is far more likely for an Egyptian princess to call her adopted son by an Egyptian name” (ibid., p. 968 n. 1:17).

29 The insistence of the Egyptian princess that Moses was literally begotten through her is clearly reflected the name she gave him. It is also consistent with the careful actions she is said to have taken to mimic the conditions of expectant motherhood, as reported by Philo: “[She] took him for her son, having at an earlier time artificially enlarged the figure of her womb to make him pass as her real and not a supposititious child” (ibid., 1:19, p. 968).

30 Note that the JST Genesis phrase “and shall be called her son” corresponds neatly to the “adoption” or “rebirth” formula or notice in Exodus [2:10]: “and he became her son.” The JST Genesis prophecy also points to the or double-meaning of Moses. The expression “her son” constitutes a pun on the Egyptian meaning of Moses in terms of ms (or mesu), “child”/“son,” as Nathan Arp has noted (N. J. Arp, Joseph Knew First). Nevertheless, the prophecy indicates that the name Moses would be a sign by which he would know that he belonged to the house of Israel (and the house of Joseph[?]). In other words, the phrase “by this name he shall know that he is of thy house” seems to indicate that the name Moses would mark him an Israelite thus implying the intelligibility of the Moses/mose/mōšeh in Hebrew also. Moses would have a “double-identity” as an Egyptian and an Israelite.

31 E. R. Goodenough, Light, pp. 292–293. See Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 1:23, p. 335 (ca. 198–203 CE). For an assessment of Goodenough’s views on ancient Jewish mysteries grounded in ritual, see J. M. Bradshaw, Ezekiel Mural, especially pp. 32–34.

32 The appearance of “Melchizedek” as two words is not consistent in the Bible and ancient texts. On the one hand, it is written as two words in the Masoretic Text of Genesis 14, Psalm 110, the Samaritan Pentateuch (S. Lowy, Principles, p. 320), the Targums (J. W. Etheridge, Onkelos, 14), and 11QMelchizedek (F. G. Martinez, Melchizedek, 2:9, p. 140). On the other hand, Samuel Zinner notes these counter-examples: “The LXX read it as one word, that is, as a name. In subtle ways we can determine that the gospels presuppose the LXX interpretation of the Hebrew text, whereas Shepherd of Hermas Command 1 seems to understand it as two words. … It is written as one word in the Genesis Apocryphon (J. A. Fitzmyer, Now This Melchizedek, pp. 312–313)” (S. Zinner, November 3 2020).

It may be possible to identify how four additional ancient authors read “Melchi-zedek,” either as a title consisting of two words or as a name consisting of one word. Zinner extends the evidence by using arguments that take into account the possibility that the numerical architecture of some biblical passages “are based on numerical values of the letters of the names of God” (I. Knohl, Sacred Architecture, p. 189). For example, the Song of Moses’ exordium (Deuteronomy 32:1-3) contains a total of 26 words, congruent with a hint at the numerical value of YHWH — namely 26 (ibid., p. 194). In an in-progress monograph (S. Zinner, Recovering), Zinner points out that:

MT Psalm 110 has a total of 65 words, congruent with the numerical value of the divine name ʾAdonai that occurs in the text. The 65 words are divided between a 2-word superscription + a 63-word main text, the result of the MT reading mlky-ṣdq in v. 4 as 2 words. By contrast, the LXX translators read in Psalm 110:4 mlkyṣdq, a single word, that is, the name Melchizedek. The LXX translators therefore counted only 62 words in the main text. The NA28 text of Mark 12:35-37, Jesus’ discussion of Psalm 110, contains 62 words. The NA28 text of the parallel in Matthew 22:41-45 also contains 62 words, despite Matthew’s significant variations in wording. The main parallel in Luke is found in 20:41-44. However, given the introductory elements gar and de in vv. 39 and 40 respectively, it seems that Luke intended these two transitional verses to introduce vv. 41-44. The parallel passage in Luke 20:39-44 shows even more variation in wording than does Matthew compared to Mark, but the NA28 text of Luke 20:39-44 also keeps the word total to exactly 62. These three examples’ matching word counts are hardly the result of chance. Arguably, they seem to indicate that the three gospel writers counted 62 words in the Hebrew text of Psalm 110, in accord with the LXX translators, and thus read not mlky-ṣdq but mlkyṣdq, i.e., the name Melchizedek. In Matthew and Mark, the discussion of Deuteronomy 6:4-5 (The Greatest Commandment) and of Psalm 110 form a single pericope. Shepherd of Hermas Commandment 1 almost doubtless has in mind the gospel pericope of the Greatest Commandment and Psalm 110. Hermas Commandment 1 in Bart Ehrman’s Loeb Greek text has a 2-word superscription and a 63-word main text, matching the MT word count for Psalm 110. Apparently, Hermas read mlky-ṣdq, not mlkyṣdq, in Psalm 110:4.

33 M. Barker, Who Was Melchizedek. That the third name in the sequence of names is meant as a title is supported by similar passages in the Visions of Amram that were reconstructed by Józef Milik. See J. T. Milik, 4Q Visions de ‘Amram, pp. 85–86; P. J. Kobelski, Melchizedek and Melchireša’, p. 28; K. Dalgaard, A Priest for All Generations, pp. 57–60.

34 M. Barker, King of the Jews, pp. 81-82, 83.

35 Note that in Israelite practice, as witnessed in the examples of David and Solomon, the moment when the individual was made king would not necessarily have been the time of his first anointing. The culminating anointing of David corresponding to his definitive investiture as king was preceded by a prior, princely anointing. See L. L. Baker et al., Who Shall Ascend, p. 353–358. See also 1 Samuel 10:1, 15:17, 16:23; 2 Samuel 2:4, 5:3; 1 Kings 1:39; 1 Chronicles 29:22. Cf. J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 519–523.

36 See Doctrine and Covenants 107:2. The various names of this order are also illustrated elsewhere in scripture: “after the order of Melchizedek, which was after the order of Enoch, which was [ultimately] after the order of the Only Begotten Son” (D&C 76:57. Compare B. Young, 26 June 1874, p. 113).

37 Doctrine and Covenants 107:4.

38 Emphasis added. See J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 53–65; B. R. McConkie, Mortal Messiah, 1:229; B. R. McConkie, Ten Blessings, p. 33.

39 Moses 1:6, 7, 40, emphasis added.

40 Satan’s first words to the prophet are “Moses, son of man” (Moses 1:12, emphasis added). In immediate response, Moses highlights the difference in title and glory between himself and his adversary: “Who art thou? For behold, I am a son of God, in the similitude of his Only Begotten; and where is thy glory that I should worship thee?” (Moses 1:13, emphasis added).

41 B. Wells, Exodus (Zondervan), Exodus 7:1. For a more extensive treatment of this topic, see J. M. Bradshaw, What Did the Lord Mean.

42 G. A. Rendsburg, Moses as Equal, p. 204.

43 W. A. Meeks, Moses.

44 Zinner observes that verse 25 in the King James Bible is verse 26 in the Hebrew Masoretic Text (counting the superscription as verse 1)—suggesting the numerical value of YHWH (26) (S. Zinner, November 3 2020).

45 See D. J. Larsen, Psalm 24, pp. 212–213. Speaking more broadly, Peter Schäfer is reluctant to take passages with similar implications taken to their logical conclusions in the medieval Jewish mystical literature “at face value” because they are so “common,” leaving one to conclude that there must be an “enormous number of deified angels in heaven” (P. Schäfer, Jewish Jesus, p. 137). However, he does concede that this is “just one more indication that the boundaries between God and his angels in the Hekhalot literature … become fluid” and that when references to individuals bearing God’s name are made, “we cannot always decide with certainty whether God or his angels are meant” (ibid., p. 137). Cf. J. L. Kugel, God of Old, pp. 5-36.

46 See D. J. Larsen, And He Departed.

47 W. A. Meeks, Moses, p. 359.

48 Ibid., p. 360.

49 Nevertheless, it must be mentioned that Jarl Fossum takes issue with Meeks’ reading, arguing that in the instances cited by Meeks name “Elohim” is “a secondary notion, derived from the original idea of his investiture with the Tetragrammaton.” See J. E. Fossum, Name of God, p. 90. For the full argument, see pp. 88–92.

50 Talon elaborates (P. Talon, Enūma Eliš, p. 27):

The importance of the names is not to be understressed. One of the preserved Chaldaean Oracles says: “Never change the Barbarian names” and in his commentary Psellus (in the 11th century) adds “This means: there are among the peoples names given by God, which have a particular power in the rites. Do not transpose them in Greek.” A god may also have more than one name, even if this seems to introduce a difficult element of confusion, at least for us. We can think, for example, of Marduk, who is equated with Aššur and thus named in many texts (especially Assyrian texts written for a Babylonian audience). He then assumes either the aspect of the One himself or the aspect of only an emanation of the One. The same occurs when Aššur replaces Marduk in the Assyrian version of Enuma Elish.

51 E. A. Speiser, Creation Epic, 7:140, p. 72. Foster elaborates (B. R. Foster, Epic, pp. 437-438):

The poem begins and ends with concepts of naming. The poet evidently considers naming both an act of creation and an explanation of something already brought into being. For the poet, the name, properly understood, discloses the significance of the created thing. Semantic and phonological analysis of names could lead to understanding of the things named. Names, for this poet, are a text to be read by the informed, and bear the same intimate and revealing relationship to what they signify as this text does to the events it narrates. In a remarkable passage at the end, the poet presents his text as the capstone of creation in that it was bearer of creation’s significance to humankind.

52 See M. L. Bowen, What Meaneth the Rod of Iron?

53 Moses 2:7.

54 JST Genesis 50:35.

55 2 Nephi 3:17.

56 Moses 1:25, emphasis added. Jeff Lindsay illustrates the resonance of this imagery with the Book of Mormon. He points out an allusion to the strength of Moses in 1 Nephi 4:2 that corresponds to Moses 1:20–21, 25 while having no strong parallel in the Bible (J. D. Lindsay, Arise, Part 1, pp. 189–190). In a personal communication, Lindsay further explains that 1 Nephi 4:2 “has Nephi urging his brethren to be strong like Moses, as if they were familiar with this concept, but the [King James Bible] has nothing about Moses being strong” (J. D. Lindsay, August 5 2019). Elsewhere, Noel Reynolds and Jeff Lindsay write (N. B. Reynolds et al., Strong Like Unto Moses):

Mark J. Johnson (M. J. Johnson, Lost Prologue, pp. 178-179) observed that the three references in Moses 1 to strength involving Moses describe a three-tiered structure “for personal strength and spirituality” in which strength is described in patterns reminiscent of sacred geography, each tier bringing Moses closer to God. The first instance depicts Moses having “natural strength like unto man,” which was inadequate to cope with Satan’s fury. In fear, Moses called upon God for added strength, allowing him to gain victory over Satan. Next, Moses is promised additional strength which would be greater than many waters. “This would endow Moses with powers to be in similitude of YHWH, to divide the waters from the waters (similar to Genesis 1:6) at the shores of the Red Sea (Exodus 14:21).” Johnson sees the treatment of the strength of Moses as one of many evidences of ancient perspectives woven into the text of Moses 1. In light of Johnson’s analysis, if something like Moses 1 was on the brass plates as a prologue to Genesis, to Nephite students of the brass plates, the reference to the strength of Moses might be seen as more than just a random tidbit but as part of a carefully developed literary tool related to important themes such as the commissioning of prophets and becoming more like God through serving Him. If so, the concept of the strength of Moses may easily have been prominent enough to require no explanation when Nephi made an allusion to it.

57 Exodus 14:21–22; Joshua 3:14–17.

58 Moses 1:25.

59 Note the plausible connection between šadday and Akkadian šadu(m) (= “mountain, range of mountains”), significant in a creation context. See D. Biale, God with Breasts. “The ancients thought of breasts as mountains, for obvious reasons, so one cannot really separate mountains and breasts in the tradition” (S. Zinner, November 3 2020).

60 Moses 2:1–2.

61 A. Marmorstein, Doctrine, p. 64 #5. In addition, the authority of God’s law, given through Moses, rested on the argument that it came “from the mouth of the all-powerful, Almighty” (ibid., p. 82 #32, emphasis added).

62 As one example of how the relevant participle is interpreted as active rather than passive, we can compare the King James Bible translation of Isaiah 63:11 (“Then he remembered … Moses”) to the Jewish Publication Society translation (“Then they remembered … Him, who pulled His people out [of the water]” [A. Berlin et al., Jewish, Isaiah 63:11, p. 909]). While it is not directly consequential to the active-passive interpretation of the name, we note a comment from the editors of the JPS Study Bible stating that “it is not clear whether ‘He [he] who pulled …’ refers to God or to Moses” (ibid., p. 909 n. 11).

63 Cf. analogous symbolism used in 1 Peter 3:18-21.

64 B. R. McConkie, New Witness, p. 529.

65 See Doctrine and Covenants 110:11.

66 W. W. Isenberg, Philip, 70:36–71:3, p. 152.

67 Moses 1;25.

68 President Russell M. Nelson has recently pointed attention to the similar role reversal reflected in the two names given to Jacob/Israel (R. M. Nelson, Let God Prevail). In reviewing this reversal, Victor P. Hamilton observes that up until his “wrestle” with God in Genesis 32, “Jacob may well have been called ‘Israjacob,’ ‘Jacob shall rule’ or ‘let Jacob rule.’ In every confrontation he has emerged as the victor: over Esau, over Isaac, over Laban”—and now, startlingly, he attempts to prevail in his conflict with God (V. P. Hamilton, Genesis 1-17, p. 334). Speaking of this “crucial turning point in the life of Jacob,” President Nelson taught:

Through this wrestle, Jacob proved what was most important to him. He demonstrated that he was willing to let God prevail in his life. In response, God changed Jacob’s name to Israel (Genesis 32:28), meaning “let God prevail.” God then promised Israel that all the blessings that had been pronounced upon Abraham’s head would also be his (Genesis 35:11–12).

69 Philo, Exodus, p. 70. For an up-to-date review of the literature on the deification of Moses, see M. D. Litwa, Deification of Moses . For more on the specifics of how this description of the deification of Moses might be understood, see J. M. Bradshaw, Ezekiel Mural, pp. 41–42, Endnote 68. See also ibid., pp. 19–21.

70 J. M. Bradshaw et al., Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham.

71 E. R. Goodenough, Light, pp. 95–96. See Philo, Giants, 54, 2:473. See C. T. R. Hayward, Israel, pp. 156–219, regarding Philo’s explanation of the name Israel as meaning “the one who sees God.”

72 E. R. Goodenough, Dura Symbolism, 9:118, 121, 122. Observes Hayward, “Philo saw nothing improper … in describing Moses as a hierophant: like the holder of that office in the mystery cults of Philo’s day, Moses was responsible for inducting initiates into the mysteries, leading them from darkness to light, to a point where they are enabled to see [God]” (C. T. R. Hayward, Israel, p. 192).

Philo said the following about his initiation: “I myself was initiated (muetheis) under Moses the God-beloved into his greater mysteries (ta megala mysteria),” and readily became a disciple of Jeremiah, “a worthy minister (hierophantes) of the same” (Philo, Cherubim, 49, 2:37).

73 E. R. Goodenough, Dura Symbolism, 10:198; see also, E. R. Goodenough, Summary, 12:190–97. Often criticized for his interpretations, Goodenough showed ambivalence in his writings about the terms “initiation” and “mystery,” speaking in his early writings in ways that at least sometimes seemed to imply a literal ritual, while in his last writings leaning toward a figurative sense of the word (R. S. Eccles, Pilgrimage, pp. 64–65).

74 J. M. Bradshaw, Ezekiel Mural.

75 C. H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Glory, pp. 212–13, 476 (emphasis in original).

76 D. Calabro, From Temple to Church.

77 C. T. R. Hayward, Israel, p. 192, emphasis in original.